In Delirious New York1, Rem Koolhaas describes a crisis in symbolic expression allegedly caused by the development of the skyscraper. First, he questions whether something “filled, from top to bottom, by business” can even be considered as a monument with symbolic content, other than as an Automonument with an “empty” symbolism that “does not represent an abstract ideal, an institution of exceptional importance, a three-dimensional, readable articulation of a social hierarchy, a memorial…”

The idea that buildings for church and state are legitimately monumental (hence having symbolic meaning) but buildings for business are not is, on the face of it, absurd. The attacks on the World Trade Center Towers in 1993 and 2001 provide some evidence that these skyscrapers for business2 (i.e., “world trade”) were symbolic of economic activity and economic power, and that precisely this symbolism was a factor in their selection as targets of terrorism. But even ordinary business towers have meaning (hence, act as symbols): the “corporate officers and the army of clerks they employed determined the meaning and usage of the tall office building” according to Roberta Moudry in her introduction to The American Skyscraper.3 Aaron Betsky is even more emphatic, stating that “Of all the buildings human beings make, towers are the most symbolic” and specifying that they “stand for the wealth and power of the commissioning agency, whether it is a developer, a private entity such as a corporation, or a (quasi-) governmental agency” (in Asia and elsewhere) or “are symbols for the transformation of Manhattan into the haven of choice for the global one percent.”4 That Betsky’s towers include both commercial and residential types does not matter in this context. And, of course, one can always cite Louis Sullivan for paeans to the symbolic grandeur of the skyscraper for business: “that the problem of the tall office building is one of the most stupendous, one of the most magnificent opportunities that the Lord Of Nature in His beneficence has ever offered to the proud spirit of man.”5

But aside from this assertion that the meaning of office towers is somehow second-class and unsuitable for monumentality or symbolism, Koolhaas makes a second claim that is equally absurd: that the height of skyscrapers makes it increasingly difficult to express internal functionality on outside surfaces, something allegedly required within the tradition of the “honest” facade in modern Western architectural culture. Koolhaas states that “mathematically, the interior volume of the three-dimensional objects increases in cubed leaps and the containing envelope only by squared increments: less and less surface has to represent more and more interior activity.”

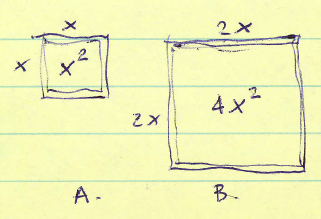

But as is clear from Figure 1, the ratio of volume and surface remains unchanged as a building gets taller. The mathematical truth is that making a building higher does not change the relationship of volume to surface; only increasing plan dimensions does that (Figure 2).

Thus this alleged crisis (“Beyond a certain critical mass the relationship is stressed beyond the breaking point…”) has nothing to do with the skyscraper or the tower — i.e., with height — but only with the size of the block. And block dimensions in Manhattan were already fixed in size with the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811.

Notes

1. Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan, Oxford University Press (New York: 1978), p.81-82.

2. Yes, it’s true that some quasi-governmental organizations, such as the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, were tenants of the World Trade Center, but the bulk of space was rented to business: see “List of tenants in One World Trade Center,” Wikipedia (accessed 2/14/17)

3. Roberta Moudry, ed., “Introduction,” The American Skyscraper: Cultural Histories, Cambridge University Press (Cambridge, New York, etc.: 2005), emphasis added

4. Aaron Betsky, “Symbolism of Skyscrapers: The Meaning of High-Rises Around the World,” ArchitectMagazine.com (The Journal of the American Institute of Architecture), July 23, 2014 (accessed 2/14/17)

5. Louis Sullivan, “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered,” Lippencott’s Monthly Magazine, March 1896, p.406 (text available here)