Even twenty years ago, conventional wisdom, reinforced by building codes, held that a vapor barrier should be placed on the warm (in winter) side of exterior walls in places like New York that have cold winters. Well, it turns out that this conventional wisdom was wrong — by 2010, Joseph Lstiburek was writing in his essay on The Perfect Wall that in virtually all climate zones, “we would split the thermal resistance of the insulation on the exterior of the structural frame with this insulation within the structural frame at least 50:50. So in an R-20 wall—at least R-10 or more on the outside of the non-conductive structural frame. And no vapor barrier on the inside of the assembly. Repeat after me, no vapor barrier on the inside of the assembly. We want the assembly to dry inwards from the control layers—and to dry outwards from the control layers. Always. Everywhere.” (emphasis added)

In other words, even if a simple psychrometric analysis showed condensation within the wall — in places where the calculated interstitial temperature dropped below the dew point temperature — the in-wall water could dry out, either to the inside or the outside. The bottom line is that such simple analyses are most often superficial, as they don’t take into account the variable permeability of certain construction materials, or the risk of trapping moisture and causing mold and rot in hot humid seasons, especially when the interior spaces are air conditioned.

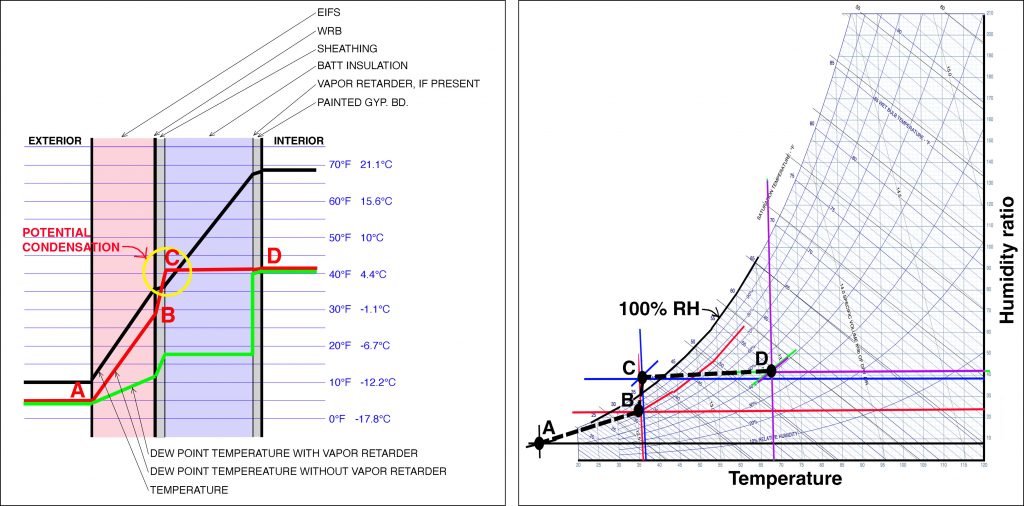

So, with the preceding paragraphs as a disclaimer, I think it is still useful — certainly as a teaching tool if not as a practical guide to construction — to understand how the R-value (resistance to conduction of heat) and inverse perm rating (resistance to the passage of water vapor) create gradients of temperature and dew point temperature within an exterior wall. If these gradients are plotted over a wall section, one can see where, and if, the temperature drops below the dew point temperature — a sign that condensation is likely. With this in mind, I have created an exterior wall psychrometric analysis calculator that finds values for temperature and dew point temperature within a user-defined exterior wall, given user-specified values for temperature and relative humidity at the exterior and interior.

Schematic wall section (left) showing interstitial temperature and dew point temperature gradients. Condensation occurs where the temperature falls below the dew point temperature. In this example, taken from the default values in the calculator, the dew point temperature — shown as a red line — crosses over the temperature between the batt insulation and the plywood sheathing, indicating the potential for condensation at this location. When a vapor retarder is added between the gypsum board and batt insulation, the dew point temperature — shown as a green line — is always below the temperature, so condensation does not occur. The psychrometric chart (right) plots the combination of temperature and humidity ratio and shows where the relative humidity rises above 100% (i.e., where condensation occurs — at point “C” in both diagrams). Images by Jonathan Ochshorn.