I led a second walking tour of the Cornell campus on August 28, 2023, focusing on Cornell’s six Pritzker-laureate-designed buildings: Milstein Hall (Rem Koolhaas), the Johnson Museum of Art (I.M. Pei), the Schwartz Center for the Performing Arts (James Stirling), Gates Hall (Thom Mayne), Weill Hall (Richard Meier), and Uris Hall (Gordon Bunshaft).

Jonathan Ochshorn addresses tour group prior to entering Bunshaft’s Uris Hall (photo by Max Rodencal)

We also visited Uris Library (William Henry Miller), Thurston Hall (Shreve, Lamb & Harmon), Upson Hall (original design by Perkins & Will, renovation by Perkins & Will with Lewis.Tsurumaki.Lewis), Duffield Hall (Zimmer Gunsul Frasca), Bradfield Hall (Ulrich Franzen), and Minns Garden. A map of the tour can be found in my blog post for the first Pritzker-plus iteration.

The following images and commentary are intended to provide context for some of my remarks on the tour, in the order of the buildings that we visited:

We started at the “bubbles” at Milstein Hall; a comparison with the arcade (atrium) at Duffield Hall is discussed later.

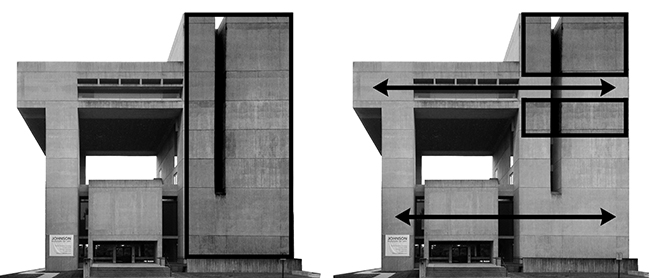

Next, we walked west to the Johnson Museum of Art and I talked about why, in the early 1970s, certain Cornell architecture faculty hated the building. Here’s an except and image from my book, Building Bad, explaining the controversy: “That the spatial logic of interior spaces should be ‘transparently’ revealed (expressed) on a building’s exterior surfaces was also a tenet of 20th-century modernism. This can be seen, for example, in the argument made by Alan Chimacoff and Klaus Herdeg in their scathing criticism of I.M. Pei’s Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University, published in Cornell’s student-run newspaper in 1973 (and, in slightly revised form, in Herdeg’s The Decorated Diagram: Harvard Architecture and the Failure of the Bauhaus Legacy, ten years later):

Hypothetically, meaning could exist in two spheres. First, the physical expression of the building’s functional organization (the famous shibboleth of Modern Architecture); second, the manifestation of an aesthetic and intellectual argument addressing itself to a range of historical and cultural issues which attach themselves to the project at hand. The Johnson Museum addresses itself to neither. With respect to the first sphere of meaning, it presents schizophrenic inconsistencies, the most blatant of which is the disposition of the gallery spaces themselves. The form of the building would suggest that the ‘great north slab’ contained spaces of similar and perhaps repetitive use, while the spaces assembled to the south of ‘the slab’ connote a contrasting, perhaps unique, set of uses. It appears contradictory that the gallery boxes are buried in ‘the north slab’ and sculpturally expressed within ‘the great void.’

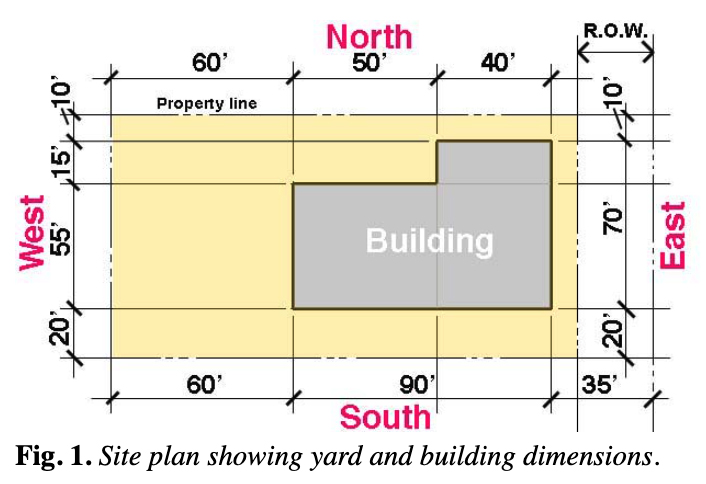

“In other words, the museum’s great crime was to have been designed from the outside, on the one hand, so that its ‘great north slab’ would, through its massing, align with historic academic buildings on the north side of Cornell’s arts quad, and, on the other hand, designed from the inside so that its complex, and somewhat contradictory, programmatic requirements could be met. Since there were not enough administrative spaces to fill the ‘great north slab’—which would have, per Chimacoff and Herdeg’s logic, given it conceptual consistency by reconciling internal programming with external form—and since the form of the ‘great north slab’ was nevertheless desired because its external massing was considered of paramount importance, per the architect’s logic, in relation to spatial patterns prevailing on Cornell’s historic arts quad, I.M. Pei employed a design strategy which allowed the exterior form to ‘respond’ to exterior conditions while allowing the interior spaces to independently ‘respond’ to programmatic requirements [see fig. 1]. Of course, it is possible that both criteria could have been met in a manner that reconciled the two imperatives. But, even so, the stipulation for such metaphorical ‘transparency’ is quite arbitrary; one could just as easily praise the museum’s design for eschewing such facile expression and, instead, embracing the contradictions of its site and program. In the final analysis, the contentiousness of arguments about the appropriateness—some might say the truthfulness—of such subjective determinations of expression is inversely proportional to the objective basis underlying the claims: nothing elicits more passionate and cut-throat criticism than arbitrary, subjective, and fleeting expressions of taste.” [Building Bad: How Architectural Utility is Constrained by Politics and Damaged by Expression, London (Lund Humphries, 2021), 107–108]

Fig. 1. Johnson museum analysis from Building Bad, p. 109.

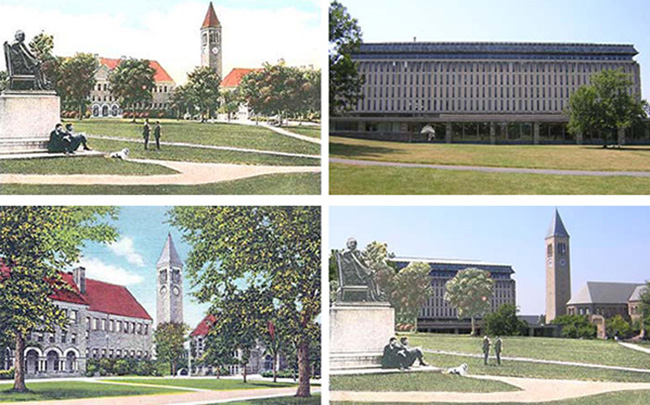

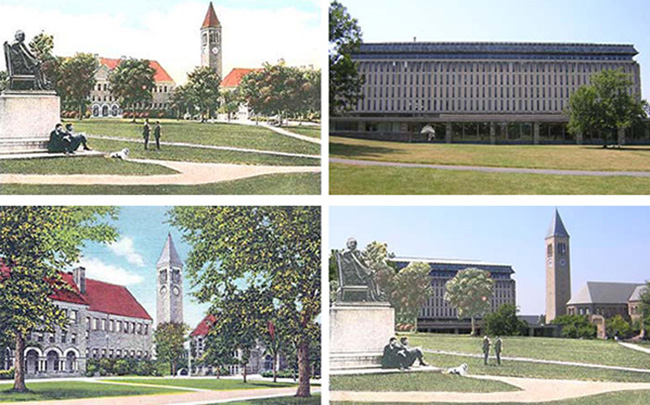

We then walked along the edge of Libe Slope to Uris Library (to see the A.D. White Reading Room). I mentioned that William Henry Miller also designed a companion building, Boardman Hall, which was torn down in the late 1950s and replaced with Olin Library. I’ve written about this disastrous decision in a prior blog post. Some images from that post are reproduced below, to give you an idea of what was lost:

Fig. 2. Boardman-Olin comparison.

Fig. 3. Boardman Hall arcade.

We then walked through the library (since the normal path was blocked by a construction fence), checked out the former “Cocktail Lounge” library addition designed by Gunnar Birkerts that was recently renovated by HOLT Architects, a local Ithaca firm, and made our way to the Schwartz Center in Collegetown. I mentioned that Stirling’s design had numerous historical references, the most important of which was Brunelleschi’s Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence:

Fig. 4. Schwartz Center – San Lorenzo comparison.

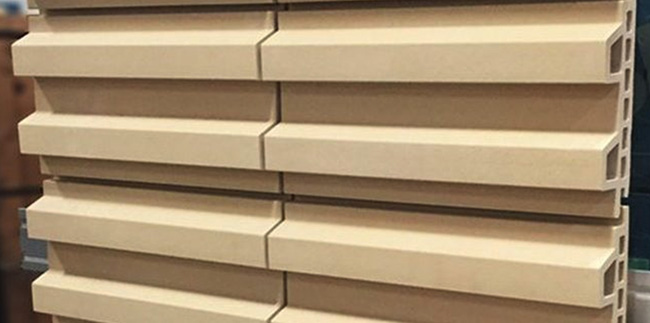

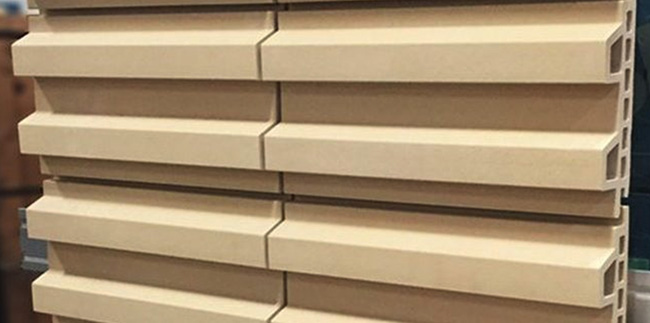

From Collegetown, we re-entered campus via the pedestrian bridge over Cascadilla Gorge and made our way into the Engineering Quad, climbing up my favorite example of a terribly designed exterior stair. We paid our respects to some rammed-earth columns (thank you Max) and then entered Thurston by way of Bard Hall, where we stopped in front of the axially-placed structures lab. From there, we entered Upson Hall, first examining the new terra cotta facade panels.

Fig. 5. Terra cotta panels, part of Upson Hall recladding.

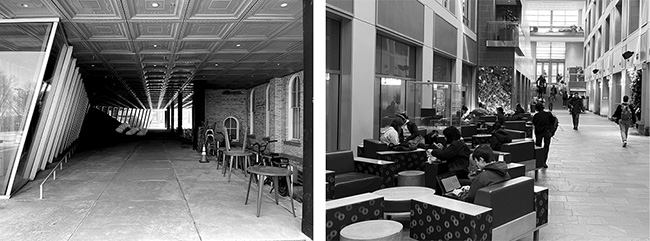

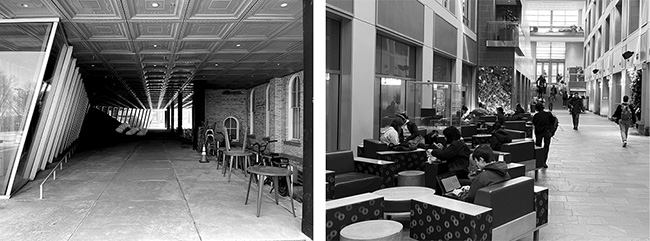

Upson took us directly into the aracde/atrium of Duffield Hall, where I speculated about a different ideological framework that informed the design of Milstein Hall’s arcade. I’ve written about this in a soon-to-be-published book: “It is instructive to compare Milstein Hall’s underutilized outdoor arcade with that of Duffield Hall, a nearby and heavily used enclosed arcade that was created between two campus building on the Engineering Quad. Both Milstein Hall and Duffield Hall were additions to existing buildings and, as such, had similar design challenges in joining a new with an existing building. Zimmer Gunsul Frasca (ZGF), the architects for Duffield Hall, activated the connection to the existing building (Phillips Hall) by creating a covered arcade bounded by Phillips Hall on one side and the new Duffield Hall on the other side. In this space, they designed useful seating areas in which students can study or collaborate in relative privacy, but with visual connections back to the main circulation spine of the arcade, so that both those seated along the perimeter of the arcade and those circulating down the middle feel active and engaged. Naturally, there is also food available, and plenty of places to sit, eat, and drink. The architects for Milstein Hall, in contrast, left the arcade space between Sibley Hall and Milstein Hall unenclosed and unpleasant, with no collaborative seating, no ability to see and be seen, no compelling activities visible in the adjacent buildings, and—as a result—with no particular reason for anyone to enter. The images in [fig. 6] show the two arcades at the same time on the same day (Tuesday, March 21, 2023, at noon), but this contrast in functionality could be demonstrated on virtually any day and any time when students are on campus.

“Koolhaas’s ‘Junkspace,’ written just a few years before OMA began the Milstein Hall project, may provide some insight into the origin of the arcade’s dysfunction, although it is risky to allege such links between the office’s theory and practice. In this article, a brilliant 7,500-word rant formatted into a single, continuous paragraph, the enclosed mall (aka Junkspace) comes under withering attack:

Junkspace seems an aberration, but it is the essence, the main thing… the product of an encounter between escalator and air-conditioning, conceived in an incubator of Sheetrock (all three missing from the history books). Continuity is the essence of Junkspace; it exploits any invention that enables expansion, deploys the infrastructure of seamlessness: escalator, air-conditioning, sprinkler, fire shutter, hot-air curtain… It is always interior, so extensive that you rarely perceive limits; it promotes disorientation by any means (mirror, polish, echo)…

“This hyperbolic descriptive text soon turns into an explicitly anti-atrium warning: “Note to architects: You thought that you could ignore Junkspace, visit it surreptitiously, treat it with condescending contempt or enjoy it vicariously… […] But now your own architecture is infected, has become equally smooth, all-inclusive, continuous, warped, busy, atrium-ridden…” And not only that, this atrium-culture fosters complacency and destroys our ability to think: “Junkspace is political. It depends on the central removal of the critical facility in the name of comfort and pleasure.” So it’s possible that this ideological posturing had some influence on the decision to leave Milstein Hall’s arcade unconditioned, uncovered, and—most importantly—without any formal or functional references to the despised prototype of the atrium/mall.”

Fig. 6. Comparison of arcades in Milstein Hall (left) and Duffield Hall (right).

Leaving the engineering quad, we walked east to Gates Hall. I talked about the use of stone or precast panels placed around normative steel columns to create a “fictional” narrative about support (in the case of Uris Hall, which we’ll see at the end of the tour) or to create an illusion of non-support (in the case of Gates Hall — see figure 7).

Fig. 7. “Fictional” support conditions at Uris Hall (left) and Gates Hall (right).

We then walked past Cornell’s Lynah skating rink (where some “snow” from the Zamboni machine had been deposited in the parking lot), and looked around Weill Hall, paying close attention to the articulated reveals between drywall, door frames, and wall tile in the first-floor bathrooms.

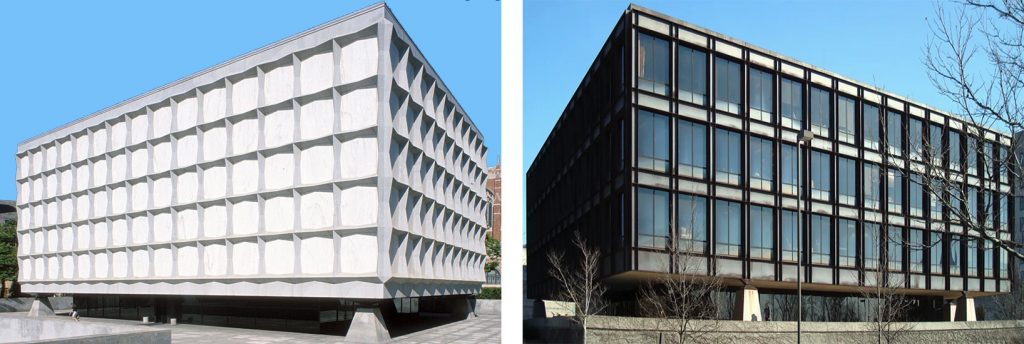

From there, we crossed Tower Road and went into what is apparently the most-hated lab building at Cornell (and one of my favorite campus buildings): Bradfield Hall. I talked about the similarity to Louis Kahn’s Richards Medical Research Lab — see figure 8.

Fig. 8. Comparison of Richards Medical Research Lab (left) and Bradfield Hall (right).

On the way to our final Pritzker building, we stopped at Minns Garden, off of Tower Road. I talked about the danger of certain forms of abstraction, comparing the vapid circles of Milstein Hall’s green roof to this garden’s rich and bio-diverse landscape design.

Fig. 9. Minns Garden at Cornell.

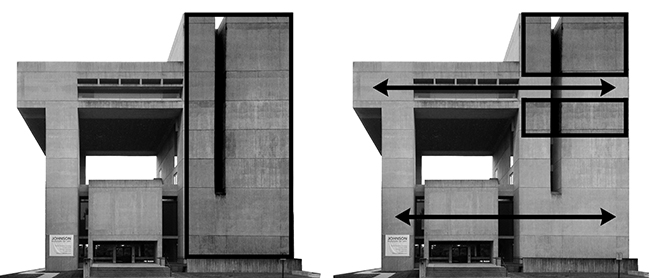

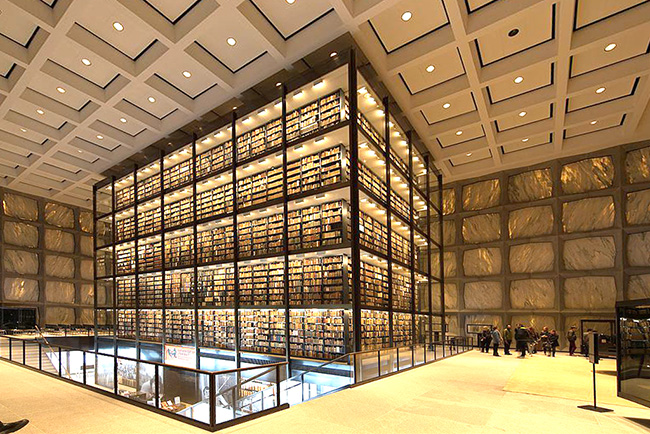

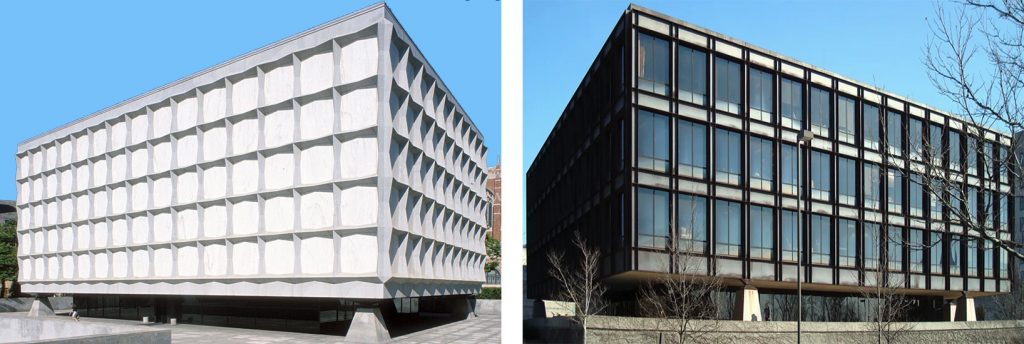

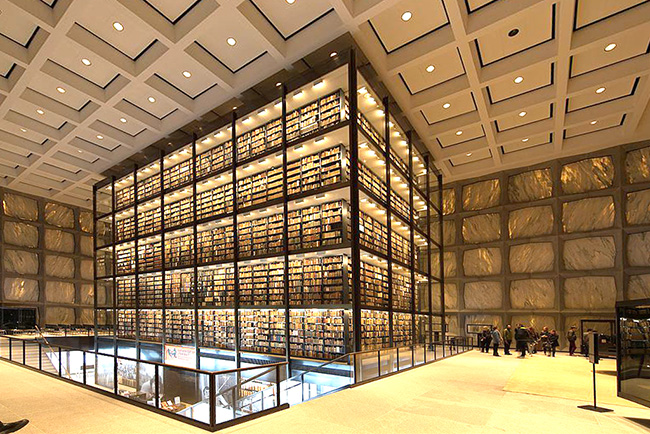

Walking west on Tower Road, we visited Uris Hall, whose exposed and expressed structure of corrosion-resistant, weathering (aka “COR-TEN”) steel is similar in its outward geometry to Bunshaft’s Beinecke Rare Book Library at Yale University, which opened about 10 years earlier (see figure 10). I mentioned that where Bunshaft’s earlier building had a more integrated design idea — i.e., the interior and exterior form had a clear relationship — see figure 11), Uris Hall’s interior was just a maze of corridors and windowless offices.

Fig. 10. Comparison of Beinecke Library and Uris Hall.

Fig. 11. Interior of Beinecke Library.

I also mentioned that the parti of Uris Hall was similar to that of Milstein Hall. As I wrote in a blog post from 2011: “Both buildings consist of large, essentially square, floor plates supported by rigid frames (vierendeel trusses) lifted off the ground and cantilevered in dramatic fashion from their points of support. Both buildings also hover over large, below-grade, auditoriums: in the case of Uris Hall, the auditorium sits politely under the podium; in Milstein Hall, the auditorium rides a reinforced concrete dome that seems to burst through the ground plane. Both buildings mediate their cantilevered steel superstructures and highly-articulated bases with a glass wrapper designed to enclose space and provide an entry at grade without compromising the visual articulation of superstructure and base.”

To prove my point, I photoshopped a portion of Uris Hall onto a photo of Milstein Hall (see figure 12).

Fig. 12. Milstein Hall (left) and a portion of Uris Hall photoshopped onto the same image (right).

We dutifully examined the maze of corridors and windowless offices in Uris Hall, after which I headed home via Collegetown while the students went to … well, wherever students go.