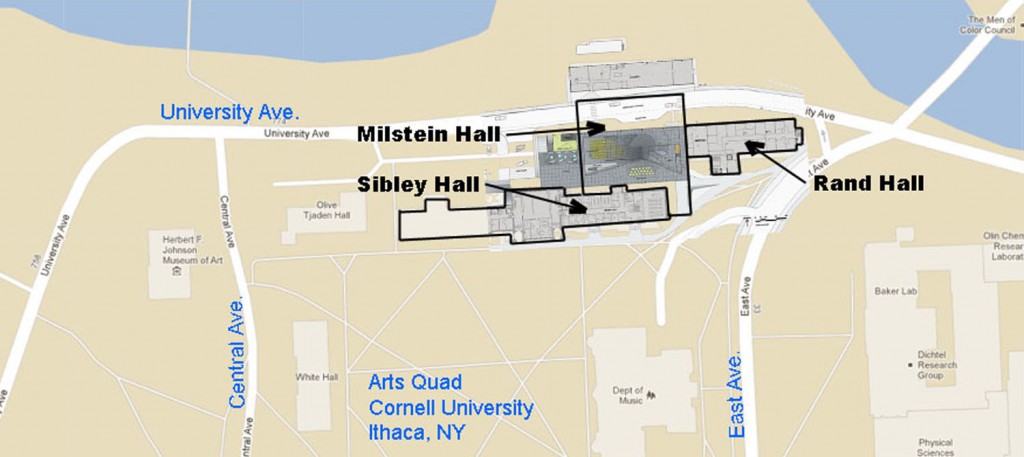

[Updated below 1/4/13] Milstein Hall (Cornell University; designed by Rem Koolhaas/OMA) has many problems, which I have discussed elsewhere. Several additional issues emerge in Ithaca’s winter weather. One, in particular, was so puzzling to me that I wrote an email to Milstein Hall’s Project Manager back in July, 2011:

From: Jonathan Ochshorn

Sent: Thursday, July 07, 2011 5:02 PM

To: xxxx

Subject: Milstein bollards

xxxx,

As you must know by now, I find many aspects of Milstein Hall puzzling. In this category, I feel compelled to mention my concerns about what appear to be steel bollards fastened to the structural concrete deck just to the west of the main Milstein Hall superstructure. I haven’t seen the working drawings for these items, so my comments may well be misinformed (I’ll take that risk).

The bollard detail seems puzzling to me on two accounts. First, the bollards seem to interrupt the rigid insulation now being placed over the concrete deck, providing a series of uninsulated pathways — thermal bridges — over the heated space below. This isn’t necessarily an energy issue, but could be a condensation issue: if humid interior air comes in contact with the colder concrete surfaces immediately below these bollards, water could condense on those surfaces, creating all sorts of problems during cold winter months.

Second, bollards are always hit by vehicles; one can observe this all over campus. By fastening the bollards to the structural deck (thereby interrupting not only the thermal protection layer but also the water, air, and vapor protection layers), it seems to me that all sorts of unnecessary problems may well occur in the future if and when a bollard is damaged by being hit. At worst, the hit could dislodge the various control layers, resulting in leaks; but even if the control layers remain intact, repairing the bollard would require an incredible amount of work, digging down beneath the upper slab, removing insulation, and then repairing all the various membranes.

It seems to me that all of these potential problems could be resolved simply by fastening the bollards to the upper slab, and allowing the insulation and various membranes to be continuous under the slab. There are also many “flexible” bollards made that accept the reality of being hit, without being destroyed or damaged.

Anyway, I hope I’m wrong about all this, and apologize in advance if my comments are, for any reason, not pertinent.

Just today, I noticed that one of the bollards appeared to be damaged in precisely the manner I had anticipated back in 2011; it’s not yet clear what the extent of the damage is, and whether the underlying waterproofing membrane has been damaged below grade.

Damage to Milstein Hall bollard, presumably during snow removal operations. Photo by J. Ochshorn Jan. 4, 2013.

Update (1/4/13): Peter Turner, Assistant Dean for Administration of Cornell’s College of Architecture, Art, and Planning, has informed me that the “damaged” bollard was actually a special removable one “to allow vehicle access.” It was kicked off its concrete base (see his photo reproduced below) but did no apparent damage to underlying waterproofing or insulation, as would be likely if one of the other bollards had been knocked over by a vehicle. Given the clear danger that some other bollard might be hit, it remains puzzling why all the bollards were not designed in a similar manner.

This special removable bollard was knocked off its concrete base, but otherwise caused no apparent damage. Photo by Peter Turner, Jan. 4, 2013.

[End of update]

Speaking of winter damage, there is another major risk factor at play in Milstein Hall due to one of its design features: there is no parapet at the boundary of the vegetated roof area, so that wind-blown snow will sometimes accumulate over the roof edge and present a hazard to pedestrians walking below. Today, the condition (see photo below) was not particularly severe, but the potential for dangerous conditions is clear.

Wind-blown snow creates potentially dangerous conditions at the edge of Milstein Hall. Photo by J. Ochshorn Jan. 4, 2013.

Finally, it is interesting to look at the classic ice dams and icicles that form each year on the Foundry, next to Milstein Hall. This building, while not officially part of the Milstein Hall project (which included some work on adjacent buildings), was renovated in anticipation of the completion of Milstein Hall. The ice dam problem (due to inadequate insulation and roof ventilation) was clearly not addressed.

Ice dams form each year on the Foundry, adjacent to Milstein Hall. Photo by J. Ochshorn Jan. 4, 2013.