The Johnson Museum has turned forty and is promoting an exhibition that ends September 1, 2013:

In conjunction with the Johnson’s fortieth anniversary, we asked architect and photographer Alan Chimacoff, Class of 1963, Arch ’64, to create a photographic essay celebrating the Museum’s architecture and its integration into the landscape of the campus and community. The Museum’s profile has become one of the iconic landmarks of Ithaca, visible from nearly every vantage point in town, so the early controversies surrounding its construction are still understandable: Would it block views from Franklin and Sibley Hall to the west? Obliterate the view of the lake from the crest of Libe Slope? Look out of place amid the New York State limestone of “Stone Row,” Morrill, White, and McGraw Halls?

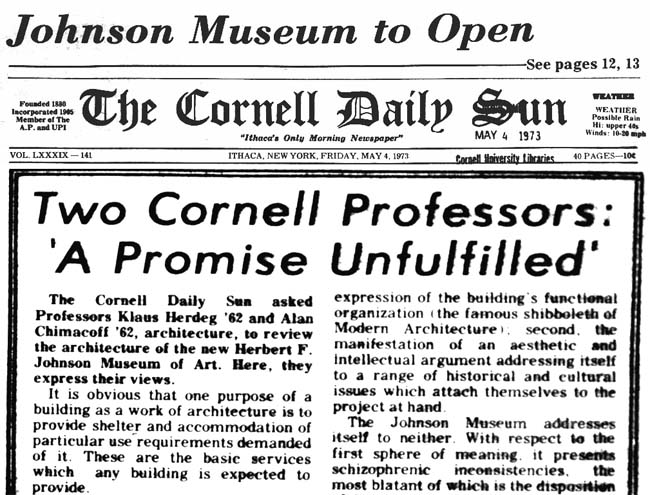

Some of the “early controversies” were actually about the quality of the architecture itself; the most notable critique appeared in the Cornell Daily Sun in 1973, written by none other than “architect and photographer” Alan Chimacoff, together with colleague Klaus Herdeg — both had been teaching in the Department of Architecture at Cornell.

I’ve transcribed the entire article as best I could from a grainy PDF in the Cornell Daily Sun archives, but Herdeg and Chimacoff’s key criticism can be understood from this brief excerpt:

Hypothetically, meaning could exist in two spheres. First, the physical expression of the building’s functional organization (the famous shibboleth of Modern Architecture); second, the manifestation of an aesthetic and intellectual argument addressing itself to a range of historical and cultural issues which attach themselves to the project at hand. The Johnson Museum addresses itself to neither. With respect to the first sphere of meaning, it presents schizophrenic inconsistencies, the most blatant of which is the disposition of the gallery spaces themselves. The form of the building would suggest that the “great north slab” contained spaces of similar and perhaps repetitive use, while the spaces assembled to the south of “the slab” connote a contrasting, perhaps unique, set of uses. It appears contradictory that the gallery boxes are buried in “the north slab” and sculpturally expressed within ‘the great void.’

With respect to the second sphere of meaning, the building offers no contribution to the ongoing polemic of Modern Architecture, into which context it purports to put itself by virtue of its employment of the contemporary stylistic vocabulary.

Klaus Herdeg went on to apply this critique to the entire legacy of Walter Gropius at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (see The Decorated Diagram: Harvard Architecture and the Failure of the Bauhaus Legacy, MIT Press, 1983). I.M. Pei, architect of the Johnson Museum, studied under Gropius at Harvard after getting his B.Arch. at M.I.T. in 1940.

Also of interest is the fact that Chimacoff, along with other Cornell architecture faculty in the early 1970s, were “fired” in a great purge described by Colin Rowe in his recollections published in 1996 by MIT Press (As I Was Saying: Recollections and Miscellaneous Essays, Volume Two — Cornellianna, edited by Alexander Caragonne):

As far as I am aware, at Cornell the only thing which I did very, very wrong was in 1967. It was in Berlin in late December; it was in Westend; it was in the house of Matthias and Lislotte Ungers; it was late in the evening and most people had left; it was gently snowing outside and I was talking to Peter Blake, both of us thinking about Matthias as a species of Galahad; and it was in this way that Peter Blake instigated my move. “Why don’t you walk down the room,” he said, “and invite Matthias to Cornell?” So I did; and, since my politics prevailed, Matthias became installed as chairman at Cornell in 1969, that fateful year of revolution following the events of Paris the year before.

But the silliest thing I ever did. For my politics were injurious not only to Matthias and myself but also to Cornell. Coming from the Berlin of Rudi Dutschke, Matthias had caught something of that ardor, that fervor to make a clean slate and, during a six-month absence in Rome which I enjoyed in late ’69, a clean slate he had become determined to make at Cornell.

Not at all necessary. Not at all to be desired. But, since he could scarcely get rid of the faculty dinosaurs, it was now the younger faculty whom he was prepared to make expendable. A very sad story; and it was hence that something like a minor holocaust ensued. He had tried to get rid of Jerry Wells while I was away in Rome but he had failed; and then, in ’71-’72, it all broke out again, resulting in the firing of Alan Chimacoff, Fred Koetter, Roger Sherwood, and in Klaus Herdeg’s disgusted resignation. Finally resulting in a charge of the dinosaurs which brought about Unger’s own withdrawal.

A footnote after the second paragraph in Rowe’s recollections contained these lyrics written by Chimacoff, “derived from Gilbert and Sullivan’s H.M.S. Pinafore, about the Ungers period as chairperson at Cornell”:

I am the chairman of this architecture school

And a very good chairman too.

I’m very, very good, but be it understood

You must never mention the name Corbu.

What never?

Well, hardly ever.

We must never mention the name Corbu.

We must never mention the name Corbu.

Then give three cheers and ring a bell

For the energetic chairman at Cornell.