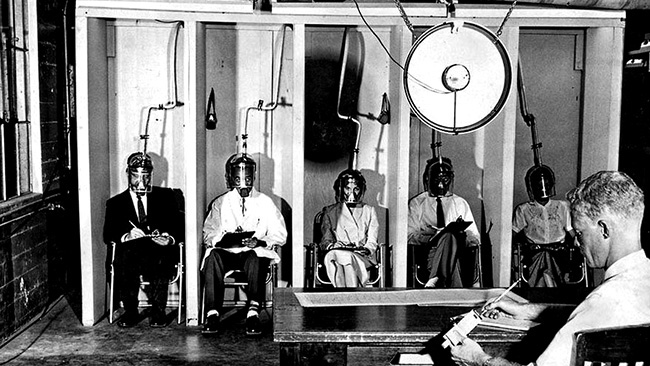

Example of human subject research (smog chamber breathing) at the Stanford Research Institute in 1956 (photo by Jack Carrick).

Cornell University is organizing an enormous research project involving human subjects that appears to violate its own guidelines—based on the so-called Common Rule promulgated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HSS)—as well as principles embedded in the Nuremberg Code of 1947 and the Belmont Report of 1979.

Specifically, Cornell is bringing together thousands of students, faculty, and staff during a global pandemic and subjecting them to in-person instruction where the risk of contracting and spreading the SARS-CoV-2 virus are high. Cornell acknowledges the risk and likelihood of serious consequences: President Pollack wrote, in her June 30, 2020 announcement of Cornell’s reactivation plans that “there is simply no way to completely eliminate risk, whether we are in-person or online; even under the best-case projections, some people will become infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and some will develop the severe form of the COVID-19 disease.” The Nuremberg Code directly prohibits such activity, stating: “No experiment should be conducted where there is a priori reason to believe that death or disabling injury will occur.”

Cornell’s own Institutional Review Board for Human Participant Research (IRB) would, in principle, evaluate such “experiments” with human subjects, but the Board has come to the conclusion that no such evaluation is required. Why? Because they claim that Cornell’s proposal to expose its human subjects to these known risks is not “research.” In an email to me on July 30, 2020, the IRB justified this conclusion as follows:

The regulatory definition of “human subjects research” has two components: the “human subjects” piece and the “research” piece. While Cornell will be obtaining information and biospecimens from living individuals through intervention and interaction (so, meeting that “human subjects” piece of the definition), the activities are not being performed for the purposes of research. Here is the “research” definition from 45 CFR 46 (the “Common Rule”):

- 46.102(l) Research means a systematic investigation, including research development, testing, and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge.

Cornell’s surveillance activities are not designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge, but rather, to track the transmission and prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 in the Cornell community, and develop practices to help curb that transmission. In addition, there is a public health surveillance activities carve-out from the Common Rule (i.e., deemed not to be research):

- 46.102(l)(2) Public health surveillance activities, including the collection and testing of information or biospecimens, conducted, supported, requested, ordered, required, or authorized by a public health authority. Such activities are limited to those necessary to allow a public health authority to identify, monitor, assess, or investigate potential public health signals, onsets of disease outbreaks, or conditions of public health importance (including trends, signals, risk factors, patterns in diseases, or increases in injuries from using consumer products). Such activities include those associated with providing timely situational awareness and priority setting during the course of an event or crisis that threatens public health (including natural or man-made disasters).

The HHS Office for Human Research Protections also published guidance on COVID-19 this past spring, which might interest you.

I hope this helps clarify our determination that Cornell’s current proposed surveillance activities do not meet the definition of “human subjects research.”

In other words, the IRB argues (1) that Cornell’s activities are not “research” because they are not “designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge,” and (2) that public health surveillance activities are, in any case, exempted from review. Both of these arguments, however, can be challenged. On the question of whether Cornell’s proposed activities constitute research, compare the HSS definition of research to Cornell’s own research statement, embedded in its reactivation plan, in which Cornell describes behavioral surveillance and surveying strategies that are designed to “provide valuable insight on subsequent guidance that could be provided to students to reduce transmission”:

Behavioral surveillance is an important tool for monitoring compliance with these directives. A standard survey instrument will be developed to observe adherence in public places (only) on campus, such as classrooms, libraries or dining facilities. In addition, Cornell will monitor infections on a daily basis. In collaboration with TCHD, Cornell Health will receive identified information of positive students and will determine activities or practices associated with becoming COVID-19 positive. Using this information, the university will be able to correlate clusters of infections in individuals sharing residences, classrooms or other activities. This may allow for the identification of places or behaviors associated with an increase in risk of transmission and provide valuable insight on subsequent guidance that could be provided to students to reduce transmission.

In an email reply to the IRB on July 30, 2020, I argued that Cornell’s intended surveillance and survey activities do constitute “research” and that the HSS public health exemption does not apply to these research activities:

First, it seems to me that Cornell’s surveillance and surveying activities are designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge. In their reactivation plan document, Cornell draws upon the results of research conducted elsewhere (for example, Cornell writes that “experiences at other institutions of higher education indicate that there will likely be individuals positive for COVID-19 among those returning to campus” — p.4). In the same way, it can be safely assumed that the results of Cornell’s surveillance and surveying will not merely be used internally but will also be disseminated. This is, by definition, a contribution to generalizable knowledge.

Second, the public health exemption does not seem to apply to Cornell’s research since Cornell’s activities are not “conducted, supported, requested, ordered, required, or authorized by a public health authority.” Cornell is collaborating primarily with Cayuga Medical Center, which is not a public health authority. It is true that Cornell is coordinating some of its reactivation planning with the Tompkins County Health Department (and TCHD is a public health authority), but this relationship is not connected to Cornell’s research on human subjects: TCHD will provide counseling to students who test positive (p.5), TCHD is conducting its own independent “syndromic surveillance system among outpatient providers in Tompkins County” (p.13), and, per state law, TCHD will conduct contact tracing. Similarly, Cornell has consulted with the NYS Department of Health Wadsworth in order to use the Animal Health Diagnostic Center (AHDC) at the College of Veterinary Medicine to expand PCR testing capabilities in Ithaca (p.3). But such ad hoc contact with public health authorities is entirely separate from the independent research—the behavioral surveillance and surveying of their human subjects—that Cornell is undertaking. And these independent research activities are not “conducted, supported, requested, ordered, required, or authorized” by TCHD or by any other public health authority.

The OHRP Guidance exception for “actions taken for public health or clinical purposes” does not seem to apply to the research activities Cornell is undertaking on its human subjects. The example given, of a hospital implementing “mandatory clinical screening procedures related to COVID-19 for all people who come to that institution” is clearly not research, as its purpose is simply to identify patients carrying the virus. Cornell’s surveillance and surveying, on the other hand, is undertaken as research, to enable “identification of places or behaviors associated with an increase in risk of transmission and [to] provide valuable insight on subsequent guidance that could be provided to students to reduce transmission.”

Third, the OHRP Guidance document, in response to this global health emergency, states: “Given the current circumstances, the research community is encouraged to prioritize public health and safety.” Yet Cornell is not reacting to a health emergency, as it was when shutting down the campus last spring. In the present case, Cornell is actually creating the public health emergency for which it has organized its research program with human subjects. The campus was shut down, and Cornell has decided to open it back up knowing that infection, disease, and—possibly—death will inevitably follow. This was a choice Cornell made, not one forced upon it. Other universities have opted not to engage in in-person instruction.

But this should not be a debate about whether Cornell made the right decision, or whether other options would have an even worse outcome. The only question here is whether Cornell’s research on human subjects should be evaluated by the IRB. I believe that the facts and definitions cited above show that Cornell’s planned activities constitute research and that this research involves human subjects.

On July 31, 2020, the IRB sent me the following reply:

The IRB staff have discussed this together with the IRB Chair, and using our collective knowledge of U.S. human subjects research regulations and the compliance community’s accepted interpretation of them, we have determined that Cornell’s surveillance activities are not research, as defined by the Common Rule. As I noted in an earlier email, if any human subjects research is proposed in conjunction with or using data from these surveillance activities, those research projects will require an IRB review.

In other words, the IRB is willing to let Cornell expose its human subjects to a highly contagious and dangerous virus, knowing that—in President Pollack’s words— “some people will become infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and some will develop the severe form of the COVID-19 disease”; is willing to let Cornell implement behavioral surveillance and surveying tools that, in Cornell’s own words, are intended to “provide valuable insight on subsequent guidance that could be provided to students to reduce transmission”; but does not consider any of this to be worthy of IRB review unless the data gathered from these activities are used in what the IRB determines is human subject research, i.e., after Cornell’s human subjects have already been exposed to a virus that is likely to cause severe disease or even death in some of the human subjects. To repeat, the Nuremberg Code states: “No experiment should be conducted where there is a priori reason to believe that death or disabling injury will occur.”

There is certainly some potential ambiguity between what constitutes research and what constitutes ordinary practice, and Cornell’s behavioral surveillance and surveying may well fall into this gray zone. However, it is precisely this ambiguity that makes IRB review essential. As argued in the Belmont Report cited above: “The general rule is that if there is any element of research in an activity, that activity should undergo review for the protection of human subjects.”

Links to all my Cornell-COVID articles are here.