[numerous updates below: 7/26/11 – 12/12/13; some nonfunctioning links re-directed Feb. 29, 2016]

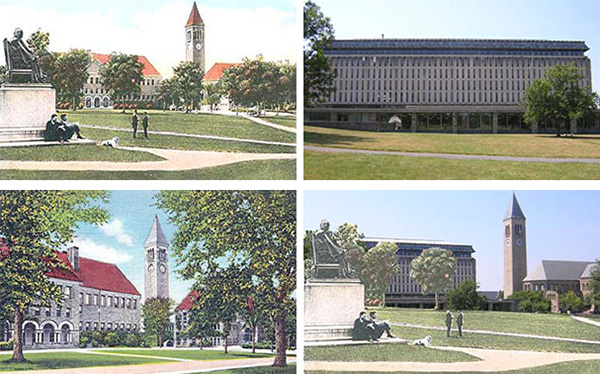

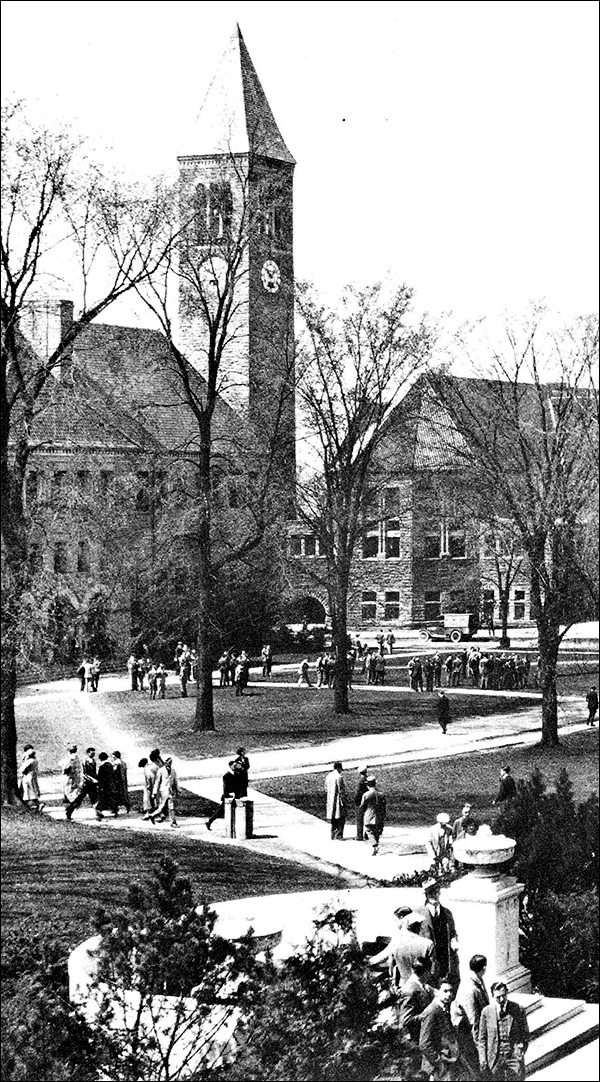

It is often necessary to anticipate future developments and trends in order to make recommendations for the renovation of building space or the construction of new space. Paul Milstein Hall at Cornell University (Rem Koolhaas, OMA architects) is an example of new construction resulting from an analysis of spatial needs. It is also an example of what can only be called a squandering of resources since these needs could have been met with far less expenditure of such resources.

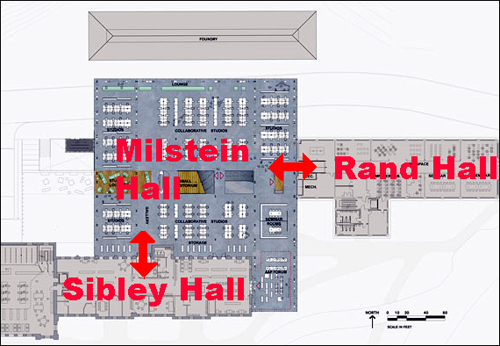

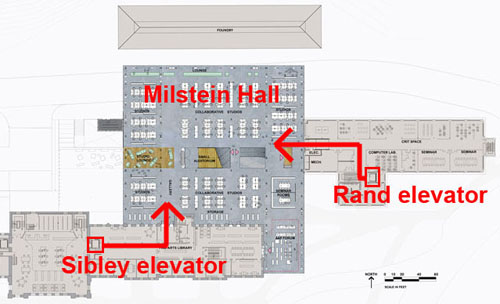

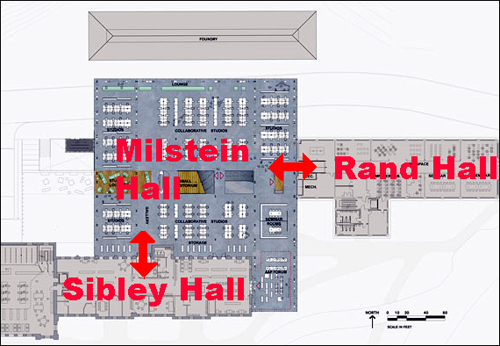

Part of what didn’t make sense in the planning of Milstein Hall was its connection at the second-floor level to the Fine Arts Library in Sibley Hall. For security reasons, this connection would have been difficult to implement, and it is likely that the doors between Milstein and Sibley Halls would have remained locked and unusable. Cornell would not permit such issues to be considered in the planning for Milstein Hall, so that the decision to link Milstein to the library space always seemed dubious.

2nd-floor plan, Milstein Hall, Cornell University

On March 24, 2010, I was called to the Dean’s office to discuss his plan to move the Fine Arts Library out of Sibley Hall, replacing it with studio space and faculty offices that are now in Rand Hall. The ultimate aim is to house the Fine Arts Library in Rand Hall. This appeared sensible for at least two reasons. First, it resolves the embarrassment of having Milstein Hall unable to connect with Sibley Hall: with design studios in Sibley and Milstein at the second-floor level, there would no longer be a security issue forcing the interconnecting doors to be locked. Second, Rand Hall appears to be a much stronger building than Sibley, which has always had problems actually supporting book stacks (unless they are spread out in an inefficient manner). Rand, on the other hand, could house books quite efficiently. In other words, Sibley has a wooden floor structure appropriate for studios, classrooms, and offices; while Rand has a steel and reinforced concrete floor system appropriate for heavier loads like libraries. [10/1/11 update: Moving the Fine Arts Library into Rand Hall is problematic for another reason. See my more recent blog post here.]

But Cornell, in its wisdom, did not plan for such a move, and will not pay for it. Apparently, the only way to accomplish this is to use money already being spent by the college to rent space on Esty Street (downtown Ithaca). By implementing an elaborate phasing plan — in which Esty St. studios are moved to Rand Hall’s first floor, displacing faculty offices which are moved into the Fine Arts Library space, displacing books which are moved either into more dense stack areas under the dome, or into the library’s annex — it seems possible to take the Esty St. rent and apply it to the limited (and temporary) renovation of Sibley and Rand Hall as described above. Ultimately, fund-raising would need to occur so that the entire Fine Arts Library (or some portion thereof that is not housed in the annex) could be moved to a suitable home in Rand Hall, with faculty offices moved again (this time to the third floor of Sibley Hall), and studios moved from Rand Hall into Sibley’s second floor as well as into the soon-to-be-completed Milstein Hall.

But this plan raises another question about the future of libraries. When I talked to Dean Kleinman in March 2010, I suggested that the general strategy of reclaiming Sibley for studios and offices seemed to make much sense, especially since the Fine Arts Library could never logically connect directly to Milstein Hall from its current location in Sibley Hall. However, I made the point that, given the rapidly fading importance of physical books in academic life, it might be wise to reconsider whether fund-raising for a new library home in Rand Hall was an appropriate use of resources. Increasingly, books and journals are accessed electronically; this trend is clearly accelerating, especially with devices like Kindles and iPads becoming available in recent years. Many academic books and journals are already available online as “electronic resources” through Cornell’s library system.

A recent article in the Cornell Chronicle dated June 29, 2010 confirms that Cornell’s engineering library at Carpenter Hall is being dismantled effective next year, since it was discovered that “approximately 99 percent of the use of the collection consists of online materials.” [UPDATE 8/13/10: two additional libraries at Cornell are being “re-imagined”: see Chronicle article here.] In fact, what stands between a fully digitized world of knowledge and the ability to gain access to that knowledge is neither technology nor resources per se, but rather an unholy alliance of forces intent on preserving the infrastructure of what is called intellectual property so that the unfettered diffusion of knowledge can continue to be held hostage to the demands of copyright owners.

Here we see before us a classic instance of the relations of production (including the legal infrastructure defining intellectual property) falling far behind the actual means of production (including the digitization of what were previously physical books and journals). It can already be seen how these relations of production are changing in response to the developing reality of the Internet. See, for example, Google vs. Viacom.

Cornell’s College of Architecture, Art & Planning’s Fine Arts Library is one of the nation’s best. Implicit in Dean Kleinman’s plan to create a new mausoleum for the Fine Arts Library’s physical collection is an attempt to preserve this competitive advantage by renovating new space for the collection. But in an age when physical collections of books will have little utility, except as objects admired in book museums, this appears to be another questionable space-allocation decision and points to the past rather than the future. Instead, Cornell should be working to accelerate the digitization of its (and all other) collections, and to participate in movements aiming for the unfettered distribution of all scholarly works in open-access networks.

[July 26, 2011 update] A just-announced partnership between Cornell and Columbia University libraries is revealing in this regard. Anne Kenney, Cornell’s head librarian, characterizes this partnership as “choosing collaboration over competition” (See Chronicle Online 7/15/11 article) as if corporate mergers — increasing market share and operational efficiencies — are ever about “collaboration over competition.” In fact, an undated article on Cornell’s library web site [link no longer works, but article can be found here, dated Oct. 14, 2009] more accurately describes the motivations and results of such a collaboration: “to achieve greater efficiencies and effectiveness” (James G. Neal, VP for Information Services and University Librarian at Columbia) and “to improve the quality of collections and services offered to campus constituencies, redirect resources to emerging needs, and make each institution more competitive in securing government and foundation support.”

The point I made in the last paragraph of this post bears repeating. Treating academic information as property, intellectual or otherwise, is simply insane. It was insane when knowledge was largely embedded in physical objects (books and periodicals) and libraries competed to have the biggest and best collections; but when knowledge is now embedded largely in digital files, the degree of insanity is impossible to exaggerate. The potential exists now to simply share all knowledge. That the Cornell and Columbia libraries (and they are hardly unique in this regard) exploit this potential as a means for competing against all others — for excluding the rest of the world from these resources — is indeed sad.

[update: March 15, 2012] Thinking of knowledge as intellectual property, and therefore as a means of competition (through which one excludes others from that knowledge to gain an advantage), is apparently the lens through which many Cornell faculty view library resources. This came to light in an article in the Cornell Daily Sun today, which stated: “According to the UFLB report, in 2010 Cornell was ranked 43rd in expenditures proportional to faculty members, 15th to students and 35th to Ph.D. fields among the 116 research libraries as assessed by the ARL.”

The idea expressed by faculty members in that article is that “our collection budget needs to stay competitive“; if not, then “we will not have the best library and won’t be successful in bringing the best faculty and students to Cornell.” That this is undoubtedly true is not the point. Rather, what is striking is the apparent lack of interest in creating a free and open-access platform where such knowledge becomes available and universal. After all, much of this knowledge is actually created by members of academic institutions, created without the expectation of remuneration and constrained in its free and universal distribution, not by the wishes of its creators, but by the archaic system of credentialing and publication that has become one of the most counter-productive aspects of academia — except, of course, from the point of view of those few institutions that are able to use this cumbersome and insane system as a means of competition against their peers.

[update: Dec. 12, 2013] Another Cornell library is being reduced in size: “…Mann Library consolidated its stacks onto its second and third floors this summer. The library based its plans to move around stacks on a study that assessed factors like the reduced need for stacks space and the need for more functional office space…” See this Cornell Sun article from Sept 29, 2013 [pdf made from this low-res archival copy].