My formal Code Appeal regarding fire-safety violations in Rem Koolhaas/OMA’s Milstein Hall at Cornell University was heard by the Capital Region-Syracuse Board of Review on July 18, 2013. I have placed extensive documentation concerning that appeal and the Board’s findings online.

I’ve requested that the Hearing Board re-examine four of the eight Exhibits that I filed earlier. My rationale is explained in the following emails [with contact information redacted], the first one sent to Charles Bliss, administrative representative of the Hearing Board:

From: Jonathan Ochshorn

Date: Wednesday, July 31, 2013 3:55 PM

To: Charles Bliss [Administrative representative of the NYS Uniform Fire and Building Code Capital Region-Syracuse Board of Review]

Cc: Mike Niechwiadowicz, Lawrence Burns, Ron Flynn, Tom Hoard, Kent Kleinman , Mark Cruvellier, John Siliciano, Gary Wilhelm, Bob Stundtner, Shirley Egan

Subject: Code Appeal – Petition Number 2013-0250

Hi Charlie,

As you know, Cornell presented its “Summary Responses” to my appeal (Number 2013-0250) at the Hearing itself, so that neither the Hearing Board nor myself had a chance to review their material ahead of time. Now that I have had a chance to actually review the handouts provided by Cornell, I would like to make some comments, and point out some problems with the Hearing Board findings that I hope can be resolved.

Regarding Exhibit 1: Cornell provided three “layout” plans for the Milstein Hall crit room showing various arrangements of tables and seats having no correspondence to the reality of the space’s actual or potential occupancy. As you know, Section 1003.2.2 of the Code states that occupancy is determined by the largest number computed in accordance with “actual” plans or “tabular values.” This means that Cornell’s submitted plans, by themselves, have no relevance in determining the required number of exits based on occupancy of the space since the tabulated values in the Code are larger.

Regarding Exhibit 2: While I disagree with the Hearing Board’s interpretation, I respect their judgment, based on the expert advice solicited by Cornell.

Regarding Exhibit 3: Proposal Request No. 129 (included as Attachment No. 3 by Cornell), which is “stamped and signed by Architect and mechanical Engineer,” does not qualify under the 2002 Code as acceptable documentation proving that the installation of sprinklers satisfies ASTM E 119. Cornell, in its handout to the Hearing Board, states: “The fire-rated windows are installed by the manufacturer and comply with the testing and their installation requirements.” Reading this, one would get the impression that the installed windows are compliant with the requirements of the 2002 Code. Of course, as was admitted in the same handout: “The Architect’s Office made an error in submittal review and changed the rating of the fire-rated window assembly from 1 hour to 3/4 hour.” Therefore, the claim that the windows “comply with the testing and their installation requirements” is only true for a 3/4 hour fire-resistance rating, and not for the required 1 hour rating. That is, the statement is both irrelevant to the issue being contested as well as being misleading, since it implies that the windows are compliant when they are actually noncompliant.

I just spoke with Ken Dias [email address redacted], an Applications Specialist at Tyco (the manufacturer of the sprinkler system), on July 23, 2013. He supported all of my objections to considering the sprinkler installation as satisfying the requirements of NER-516; i.e., he agreed that these openings do not count as 1-hour fire-resistance-rated walls per ASTM E 119. In an email to me dated July 24, 2013, he writes: “You have stated that there is a horizontal mullion projecting more than 5/8″ from the glazing. It is likely that this horizontal mullion would impede the smooth continuous flow of water down the glazing and create unacceptable dry spots. Again, horizontal mullions are not allowed in accordance with the UL Specific Application Listing… You have stated that the wood framing from the original window is less than 2″ from the new glazing. The UL Listing requires that all combustible material must be a minimum 2″ from the face of glazing… Lastly, this installation is quite unique in nature as it encompasses a ‘new’ piece of glazing located off of an existing window, resulting in an ‘enclosed’ area between two pieces of glazing where one of the two WS sprinklers is located within. This arrangement was not considered in the UL testing nor is it addressed within the evaluation service reports. It should be understood that the intent of the WS Window Sprinkler is to realize activation in a timely enough manner to protect the associated glazing. The existence of two panes of glass on either side of the one WS sprinkler will result in the prevention of hot gasses to that sprinkler until such time that the original pane may rupture. Consideration should be given to what will happen to the rupturing pieces or sections of glass. Could large pieces somehow be propped up against the newer pane, causing an obstruction to the smooth flow of water down this pane?”

The Tyco specialist concludes his email as follows: “In conclusion, this installation does not appear to be in compliance with the UL Listing per Tyco data sheet TFP620, ESR-2397 or NER-516″ (emphasis added).

Cornell, in its testimony and handouts, has been extremely misleading, if not outright dishonest, in claiming that the fire barrier satisfies Code requirements. The “signed and sealed” drawings are simply engineering drawings for a sprinkler application, and, as far as I can tell, say nothing at all about satisfying requirements for a 1-hour fire rating, per NER-516 or ASTM E 119. The claim that the horizontal mullion is compliant because it is only a “muntin” seems to be a complete fabrication, with no basis in any documentation. This claim is explicitly contradicted by the technical specialist at Tyco, the manufacturer of the sprinklers. Cornell’s claim in their handout that the “fire-rated windows are installed by the manufacturer and comply with the testing and their installation requirements” is absolutely misleading and disingenuous, as these windows only provide a 3/4-hour fire-resistive rating rather than the required 1-hour rating.

The fire-barrier is also problematic in that only one-sided sprinklers were apparently installed on the basement and first-floor levels, based on requirements for exterior wall protection, rather than for fire barrier separation requirements. Yes, these are “exterior walls,” but the protection needed is not exterior wall protection; rather, since the exterior spaces under Milstein Hall count as building area, the required protection is for fire barriers, and the sprinkler installation should have been two-sided.

Regarding Exhibit 4: I disagree with the Hearing Board’s findings, but respect their determination that the lobby/bridge constitutes a mezzanine within the crit space.

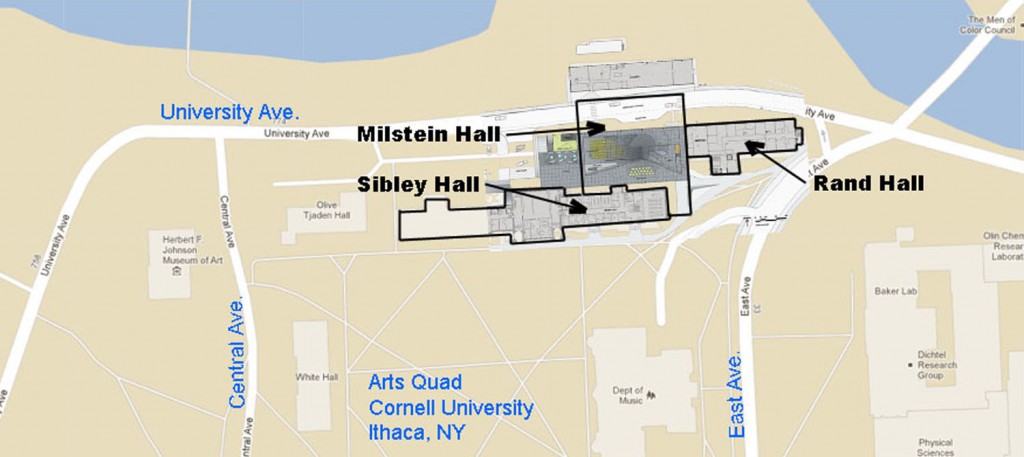

Regarding Exhibit 5: As far as I can tell, the only thing upheld by the Hearing Board in its ruling on Exhibit 5 is that a fire barrier under Appendix K does allow an addition to increase the area of an existing building beyond that permitted by Chapter 5 of the Code. However, the Hearing Board, in their findings, agreed with me that the entire building consisting of Sibley, Milstein, and Rand Halls counts as Type V-B construction, based on the construction type of Sibley Hall.

The question remains as to what limits should constrain the area of such an addition. Lawrence Burns of KHA Architects answers this question in his letter reproduced as Attachment No. 4: “We believe that the requirements of nonseparated uses applies [sic] to each portion of the building and do not restrict the areas of the entire building” (emphasis added). Cornell, in their handout to the Board, makes the same point. In other words, Milstein Hall’s per-floor area, taken by itself, must still meet the requirements for nonseparated uses in the 2002 Building Code.

Therefore, even though the Board upheld the City of Ithaca Code Officials’ determination (agreeing with the City that an addition can increase the area of an existing building if separated by a fire barrier), the Board disagreed with the contention made by Cornell and the City of Ithaca that fire barriers used under Appendix K allow each fire area to be designed according to its own construction type. By insisting that the entire building be designed with construction type V-B, the Board ruling effectively establishes that Milstein Hall, all by itself, must not exceed per-floor area limits of the Code. Since Milstein Hall — considered by itself without the added area of Sibley or Rand Halls — still exceeds those area limits, it is clearly noncompliant. This is because Chapter 5 of the Code sets a per-floor area limit for nonseparated B/A-3 occupancies with Type V-B construction of 6000 square feet, which can be increased to no more than 22,500 square feet when sprinklers and the maximum possible frontage allowances are factored in. Because Milstein Hall has floor area of 25,600 square feet, it exceeds this limit and is therefore noncompliant.

Regarding Exhibit 6: Cornell has recently posted an occupancy sign in Milstein Hall’s upper level with a 530 occupant limit, thereby requiring 3 exits. There are only two compliant exits for this space, and only two exits are shown in the construction documents. The “new” change in occupancy, from “B” to combined “A-3 and B” uses, should have triggered a new building permit application under the 2010 Existing Building Code, as it apparently occurred well after Milstein Hall was completed and after a Certificate of Occupancy was issued. In any case, the new “third” exit is noncompliant for at least two reasons: it has no exit sign, and the stair in Rand Hall to which it leads violates Section K901.2 in the 2002 Code (assuming that the old Code governs), in that the addition (Milstein Hall) extends nonconforming aspects of the existing building (the exit stair).

Regarding Exhibit 7: There are a number of errors in Cornell’s handout and testimony about Room 261 in E. Sibley Hall. First, it is absolutely inappropriate and dangerous to compute the remoteness of exits within a room or area by looking only at the remoteness of exits for the building as a whole. The plan provided in Cornell’s handout shows only the remoteness calculation for E. Sibley Hall as a whole, but not for Room 261. The idea that this room “is part of a larger space with two remote exits,” and therefore does not need to satisfy exit requirements for its own occupancy, is so completely wrong-headed and dangerous that I find it hard to believe that such statements would be put in writing by both the architect of record and the architect managing the project for Cornell.

Cornell’s plan, provided in the handout, further states that “Door 1, 2, and 3 can be opened into Milstein Hall.” First, this is factually inaccurate, as these doors are almost always locked (they are locked right now as I type this email). Second, having doors that “can be opened” is not a sufficient specification for a legal exit. For one thing, there are no exit signs marking these doors as exits; and there is no special hardware that guarantees that the doors remain unlocked (in fact, as I have just written, the opposite is true). Third, such exits would create new exiting conditions in Milstein Hall that were not part of the permitted set of drawings. A new building permit would be required and new exiting calculations would need to be provided before the doors leading from Room 261 to Milstein Hall can be used as exit doors from Sibley Hall.

Wilhelm’s testimony described the posted occupancies in Room 261 as a relic of the original pre-Milstein era, presumably when the space was occupied by the Fine Arts Library. Wilhelm stated that this posted occupancy was not something newly contrived, but rather a lingering remnant of the old occupancy. But a library stack area has a load factor of 100 square feet per occupant, or only 17 occupants for the entire room. This clearly has no relationship to the posted occupancy of 112 or 240 persons. In fact, the posted occupancy sign in Room 261 was not only recently created, but it was revised at least twice within the past year or so — well after Milstein Hall was completed.

As it was edited and re-posted after May 9, 2012, it is clearly something done deliberately — well after the certificate of occupancy for Milstein Hall was issued on Feb. 24, 2012. It therefore should have triggered a code review under the Existing Building Code of NYS, since all changes of occupancy — even those within the same A-3 occupancy class — require Code review. Increasing the occupancy of a space from 100 square feet per occupant to 7 square feet per occupant, and thereby increasing the occupant load in the room from 17 to 300 (subsequently changed to 240) clearly is something that the Building Department should have reviewed, especially in a space with only a single legal exit.

Regarding Exhibit 8: I have already discussed the flaws in the so-called analysis provided by the architects of record for the move of the Fine Arts Library into Rand Hall’s third floor. One new claim, however, needs to be rebutted: Cornell’s handout to the Hearing Board [page eight] states that the floor-ceiling assembly separating the floors of Rand Hall is “a reinforced concrete which is accepted as an archaic 1-hour assembly.” In fact, the floor structure of Rand Hall consists of steel girders and beams which have no fire-resistive rating, as their bottom flanges are exposed and have no fire-proofing. Reinforced concrete slabs are supported by these steel beams, but in no way provide a 1-hour fire-rated separation, “archaic” or not.

I hope that the Hearing Board can re-visit these issues, based on the fact that Cornell provided inaccurate or misleading testimony in a number of instances, and provided no opportunity for these claims to [be] reviewed before the Hearing itself. I think it is important to get this right, as the safety of hundreds of students, faculty, and staff is at stake, as is the integrity of the Code process.

Jonathan Ochshorn

I then received a copy of this rather nasty letter (373 KB screen-resolution PDF) from Shirley Egan, Cornell’s Associate University Counsel. Its argument is entirely procedural; there is no attempt to address the actual fire-safety concerns that I raised.

Realizing that Cornell might attempt to keep using the noncompliant Crit Room space with only a single exit, in spite of the Hearing Board’s finding sustaining my argument that multiple exits were required from a room with so many potential occupants, I sent the following, shorter email to Charles Bliss:

From: Jonathan Ochshorn

Sent: Tuesday, August 06, 2013 2:58 PM

To: Bliss, Charles [Administrative representative of the NYS Uniform Fire and Building Code Capital Region-Syracuse Board of Review]

Cc: Mike Niechwiadowicz, Lawrence Burns, Ron Flynn, Tom Hoard, Kent Kleinman , Mark Cruvellier, John Siliciano, Gary Wilhelm, Bob Stundtner, Shirley Egan

Subject: Re: Code Appeal – Petition Number 2013-0250

Hi Charlie,

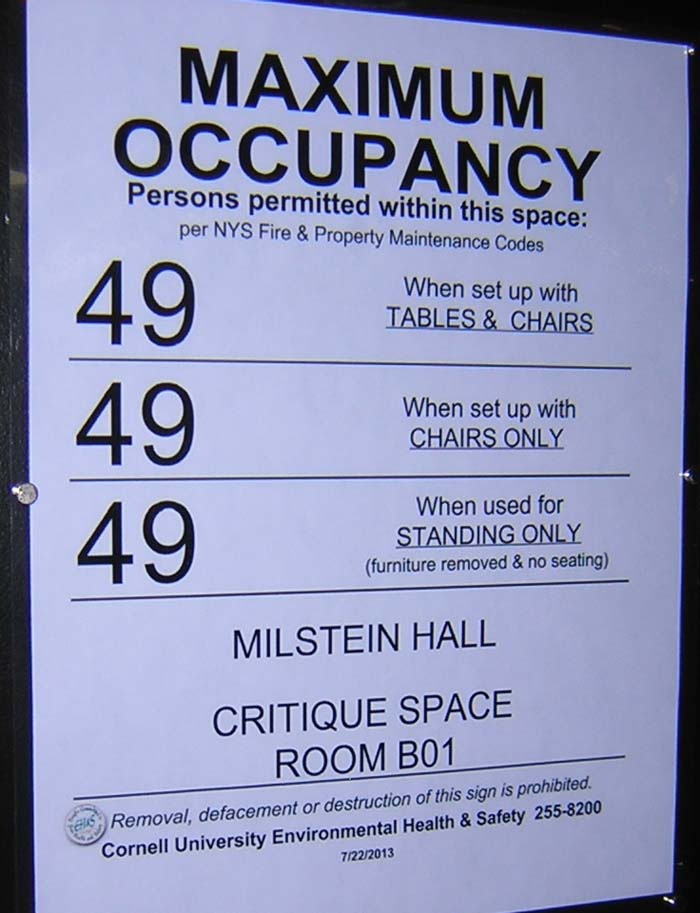

Cornell, in its “explanation” about the occupancy of the crit room (Exhibit 1), claims that it can be designed with an occupant load of 100 square feet per occupant, when used as a classroom/critique space Group B occupancy. This is how they arrive at their figure of “49 or fewer persons” and their conclusion that, when used as a classroom/critique space, only one exit is required.

This is a fundamental misreading of the Code: it confuses the occupancy class (in this case Group “B”) with the actual use of the space. The 2009 IBC Code and Commentary confirms the importance of this distinction: “Table 1004.1.1 [Table 1003.2.2.2 in the 2002 Code] establishes minimum occupant densities based on the function or actual use of the space (not group classification)… While an assumed normal occupancy may be viewed as somewhat less than that determined by the use of the table factors, such a normal occupant load is not necessarily an appropriate design criterion. The greatest hazard to the occupants occurs when an unusually large crowd is present.” (emphasis added)

In other words, the use of 100 square feet per occupant — a number appropriate for actual “business use” — is not appropriate for a classroom/critique space, where the density of occupants is far greater. Whether a value is chosen based on “classroom” use (20 square feet per occupant), unconcentrated assembly use (15 square feet per occupant), or some other rational value, it is clear that far more than 50 people can occupy the space, and that at least two exits are needed, even when the space is configured for critiques.

Jonathan Ochshorn

Charles Bliss then advised me that I could ask the Hearing Board to reopen the case:

From: Charles Bliss [Administrative representative of the NYS Uniform Fire and Building Code Capital Region-Syracuse Board of Review]

Date: Tuesday, August 6, 2013 4:20 PM

To: Jonathan Ochshorn

Cc: Mike Niechwiadowicz, Lawrence Burns, Ron Flynn, Tom Hoard, Kent Kleinman , Mark Cruvellier, John Siliciano, Gary Wilhelm, Bob Stundtner, Shirley Egan, Thomas Romanowski (DOS), Brian Tollisen (DOS)

Subject: RE: Code Appeal – Petition Number 2013-0250

I have not yet had the time to review your documents. You have the option of asking the Board to reopen the case based upon new information. That would take place at the next hearing which would probably be in September. If the Board will not reopen the case, then your next option is to file an Article 78 proceeding against the State.

Charles P. Bliss, PE

I responded with the following email, requesting that the Hearing Board reopen the case:

From: Jonathan Ochshorn

Date: Tuesday, August 6, 2013 5:10 PM

To: Charles Bliss [Administrative representative of the NYS Uniform Fire and Building Code Capital Region-Syracuse Board of Review]

Subject: Re: Code Appeal – Petition Number 2013-0250

Hi Charles,

I would like the Board to reopen case number 2013-0250 and reconsider Exhibits 1, 3, 5, and 7. Do I need to make a more formal request, or is this email sufficient?

Even though the Board sustained my argument regarding Exhibit 1, I remain concerned that Cornell appears to believe that the Hearing Board’s ruling supports Cornell’s intention to maintain only a single exit in the “crit room” space, as described in my prior email dated August 6, 2013 [copied above]. I request that the Board examine, and rule on, Cornell’s contention that one exit is sufficient for Group “B” occupancy.

Regarding Exhibits 3 and 7, I believe that Cornell provided misleading and inaccurate handouts and testimony, as described in my prior email dated July 31, 2013 [copied above]. I would like the Board to reconsider their ruling in light of new evidence concerning this misleading testimony.

Regarding Exhibit 5, I request that the Board clarify its ruling. If Sibley-Milstein-Rand Hall is a single building with a V-B construction type, as the Board stated in its findings, then it appears that Milstein Hall, even evaluated under the Board’s reading of Appendix K in the 2002 Code, is noncompliant.

Jonathan Ochshorn