There are many problems with Cornell’s reactivation plan. Consider the following (page numbers refer to the PDF linked above):

1. Probably the most serious problem with Cornell’s plan is its stated intention to conduct research on its own human subjects, in apparent violation of protocols established by the Institutional Review Board for Human Participant Research (IRB): see the IRB’s “decision tree.”

Cornell outlines its human-subject research goals in the plan itself, describing how behavioral surveillance and the use of survey instruments will enable researchers to determine which activities or practices—that Cornell itself has put into place—are associated with viral infection with SARS-CoV-2. Knowing that its practices will have a high probability of spreading infection (Cornell President Pollack wrote, in her June 30, 2020 announcement of Cornell’s reactivation plans: “There is simply no way to completely eliminate risk, whether we are in-person or online; even under the best-case projections, some people will become infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and some will develop the severe form of the COVID-19 disease”), Cornell seeks to gather statistically valid information that can only be obtained by placing its human subjects in jeopardy (p.12–13):

Behavioral surveillance is an important tool for monitoring compliance with these directives. A standard survey instrument will be developed to observe adherence in public places (only) on campus, such as classrooms, libraries or dining facilities. In addition, Cornell will monitor infections on a daily basis. In collaboration with TCHD, Cornell Health will receive identified information of positive students and will determine activities or practices associated with becoming COVID-19 positive. Using this information, the university will be able to correlate clusters of infections in individuals sharing residences, classrooms or other activities. This may allow for the identification of places or behaviors associated with an increase in risk of transmission and provide valuable insight on subsequent guidance that could be provided to students to reduce transmission.

[Updated July 29, 2020: Not surprisingly, Cornell’s IRB has determined that “the public health surveillance work currently proposed by Cornell does not meet the regulatory definition of human subjects research, and, therefore, does not require IRB review or approval.” (Email to me from Senior IRB and COI Administrator, dated July 29, 2020). Added July 31, 2020: see my detailed blog post on Cornell’s human subject research.]

2. In describing local medical capacity (p. 3) Cornell states that “Cayuga Medical Center has 212 beds and its three-phase surge plan would increase capacity for a total of 318 critical care and ICU beds and 50 ventilators.” Yet, it is well known that effective treatment of COVID-19 is not only constrained by the number of beds or ventilators, but also by the number of doctors and nursing staff. Cornell does not say how many such trained personnel are available locally.

3. Cornell suggests that “faculty who wish to meet with advisees in person may do so, provided they are able to maintain strict distancing, wear masks and keep their office doors open (for air flow and to increase compliance with health precautions).” (p.6) While modern building codes have eliminated the requirement for fire-rated corridors and self-closing fire-rated doors in many cases, there are still instances where such advice (to “keep office doors open”) would violate fire-safety regulations.

4. Cornell references the ASHRAE guidelines for restarting operations—dealing primarily with HVAC and related systems—but both ignores and contradicts their recommendations in at least one of Cornell’s linked (and restricted1) documents, stating: “Restore all set-points and scheduled modified during NY-pause.” In other words, the advice is to return to “business as usual” by restoring default set-points, rather than disabling certain default conditions to provide more fresh air circulation. The ASHRAE start-up checklist mentions things like flushing out buildings, and so on, which are not mentioned at all in Cornell’s version.

Where Cornell does repeat some of the AHRAE guidelines that contradict this advice to return to default settings—for example, to disable demand control ventilation (p.8)—there is no mention of the fact that providing sufficient outdoor air in some buildings may not even be possible, since existing HVAC equipment may be incapable of dealing with the extra loads caused by the use of more effective filters (MERV-13 or better) and high humidity associated with the conditioning of outside air (at least in summer; this problem could be reversed in the winter). Where are the actual metrics on a building-by-building, or even a space-by-space basis? Faculty, students, and staff have no idea about the number of air changes per hour (of fresh air) that will be provided in academic buildings and classrooms.

5. Cornell states that “vulnerable” faculty are being “urged” to avoid in-person instruction (p.9): “According to the World Health Organization, people of all ages can be infected by COVID-19. However, individuals over 65, as well as individuals with preexisting medical conditions (such as asthma, diabetes, and heart disease) or compromised immune systems are considered to be at higher risk. While the university cannot compel individuals in higher-risk categories to avoid in-person instruction or other work, the university will urge these individuals to do so.” This is, simply, not true. Faculty (myself included) have never been “urged” to avoid in-person instruction, neither at the university, college, nor departmental level. I’ve received scores of emails from provosts, presidents, deans, and department chairs, none of which suggested that I should not teach in-person because I’m 68 years old. In addition, the statement ignores the obvious fact that even younger faculty who become infected face serious risks to their health, and also risk spreading infection to other household members who may well be more vulnerable than they are. The truth is that the various administrative missives I’ve received often contain an implicit request that more faculty volunteer to teach in-person, since the university’s financial model depends upon having enough in-person instruction so that they can promise students who return to campus that they will have at least one in-person teaching experience.

6. Cornell claims to have booked 1,200 local hotel rooms “for various blocks of time” to provide for isolation or quarantine if needed. But what does this actually mean? Over the course of the summer and the fall semester, there are approximately 100 or more days (let’s say 100) which means that Cornell could have booked a mere 12 hotel rooms per day and met its goal of reserving 1,200 hotel rooms “for various blocks of time.” So how many rooms are actually available on any given day? Is the number 12 rooms per day, or 24 rooms per day, or something else? Cornell doesn’t say.

7. Cornell, in one of its bullet points (p.16) talks about how often its buildings will be cleaned, referring to “frequent cleaning and/or disinfection of high-touch surfaces …” This “frequent” cleaning turns out to be just once a day, except that “high-touch items such as light switches, door handles and push bars, elevator call buttons and handrails … will be sanitized twice per day” (p. 10). One has to wonder about the seriousness of Cornell’s reactivation plan if they can state that wiping down a door handle twice a day is part of a viable strategy for controlling this virus.

Actually, my own experience with Cornell and hygiene, in a related context, may be of interest. See Appendix below.

Appendix

I raised the issue of poor sanitation practices in Cornell’s fitness centers more than a decade ago, in September, 2009. After more than two years of follow-up complaints, Cornell’s solution was, and remains, highly problematic. There are still no sinks for hand-washing in Teagle or Helen Newman Hall fitness centers, and no mandatory wipe-down protocols for equipment. The paper towel dispensers and Simple Green All-Purpose Cleaner that were provided are patently inadequate, especially since this particular cleaner is useless against transmission of the virus causing COVID-19. Here is my initial email complaint from 2009:

On 9/8/09, 7:29 AM, “Jonathan Ochshorn” <jo24@cornell.edu> wrote:

TO: fitness@cornell.edu; Thomas W. Bruce <vpcommunications@cornell.edu>; Gannett Health Center <gannett-mailbox@cornell.edu>

The fitness centers at Cornell (I only refer to Helen Newman and Teagle) should take more account of hygiene, especially given the incidence of flu this season. Gannett has written: “HELP STOP THE SPREAD: Watch for seasonal flu vaccine late this month or early October. Currently, flu prevention consists of getting adequate rest and nutrition, and practicing excellent hand hygiene.” (www.gannett.cornell.edu). <http://www.gannett.cornell.edu/>

There is no access to water for washing hands in the two fitness centers refer to, and no non-water hand-washing options are made available.

There is no systematic process for cleaning the equipment after each use. The current policy of intermittent cleaning is useless. It is essential that the equipment be cleaned after each use. This cannot be voluntary or discretionary.

At the point where uniforms and towels are issued, “fresh” towels are placed on the same counter as “soiled” towels. Personnel do not seem to have a systematic protocol in place for the sanitary transfer of soiled uniforms so that they do not contaminate the fresh ones. They also seem to put themselves at risk.

If Cornell is serious about reducing the spread of disease, please don’t just issue emails: take productive and effective action.

Thanks.

Jonathan Ochshorn

Associate Professor

After two years of repeated follow-up emails, Cornell, in early 2012, finally agreed to set up a committee of in-house people to figure something out, which ultimately resulted in the paper towel dispensers and Simple Green Cleaner. I responded to this “solution” later in 2012:

From: Jonathan Ochshorn <jo24@cornell.edu>

Date: Thursday, November 29, 2012 at 12:17 PM

To: Beth McKinney <bm20@cornell.edu>

Cc: Janis I Talbot <jit1@cornell.edu>, Tisha Lea Tipping <tlt29@cornell.edu>

Subject: Re: Fitness Follow Up

Beth,

Some follow-up on the issue of sanitation practices at the Cornell fitness centers:

Providing cleaning materials for fitness center users is an improvement. However, by leaving it as a voluntary activity, the transmission of infections — which affects the entire Cornell community — is not addressed. This is because very few users seem to be using the available cleaning material. It really needs to be made mandatory, and an educational component needs to be built into Wellness (or other) memberships.

The actual materials provided are not satisfactory. The paper towels fall apart when used; the blue cloth towels work much better, but I was told yesterday that they are not available for users, only for staff. And no cleaning materials have been provided for the floor mats.

Finally, the poor sanitary practices at the issue rooms (at least in Teagle) persist: clean towels and gym uniforms are placed on the same counter surfaces with soiled uniforms and towels. While the issue rooms may not be within your jurisdiction, it seems to me that sanitation practices should be coordinated centrally — someone needs to take the initiative to provide a consistently safe exercising and fitness environment.

Thanks again for your interest in these issues.

Jonathan Ochshorn

In the end, Cornell just said no: supplying paper towels and Simple Green Cleaner was all they were prepared to offer:

From: Beth McKinney <bm20@cornell.edu>

Date: Friday, November 30, 2012 at 2:35 PM

To: Jonathan Ochshorn <jo24@cornell.edu>

Cc: Janis I Talbot <jit1@cornell.edu>, Tisha Lea Tipping <tlt29@cornell.edu>, Kerry Howell <kk253@cornell.edu>, “Frank A. Cantone” <fac2@cornell.edu>, Mary J Adams-Kucik <mja12@cornell.edu>, Mark Joseph Bilyk <mjb17@cornell.edu>

Subject: RE: Fitness Follow Up

Dear Jon,

I am happy to reply to your concerns on behalf of Cornell Fitness Centers, Gannett Health Services and Environmental Health and Safety.

We appreciate your conscientious efforts to help the fitness centers minimize the spread of infections. The team that was created to address these concerns consisted of representatives from the Cornell Fitness Centers, Gannett Health Services, CU Wellness Program, Recreational Services, and Environmental Health and Safety. After several meetings, these subject matter experts agreed the most effective way to mitigate the problem was to provide what you currently see in the fitness centers.

At this time, we remain firm that the current procedure has improved the situation and is working well for our members. There is nothing more that our group plans to change at this time.

I will, however, let Mark Bilyk, who oversees the issue rooms, know about your concerns regarding the issue room procedures.

Best,

Beth

Note:

1 Following the link on p.7 to “please visit Cornell’s Environment, Health and Safety website,” we are taken here. I went to the “Facilities Start-up Checklist” since it seemed to correspond to ASHRAE’s start-up advice, but the site required a Cornell netID. Yet, where ASHRAE’s start-up advice was comprehensive and nuanced, the Cornell start-up advice was generic and incomplete.

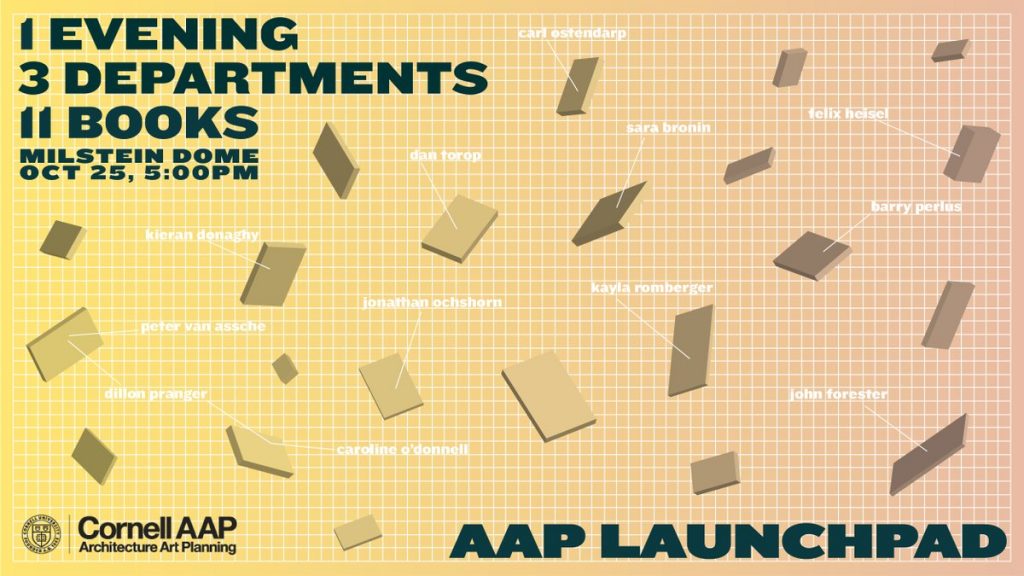

Links to all my Cornell-COVID articles are here.