I recently found the type-written original copy of my first “scholarly” paper, written in 1983 and rejected for publication in the Journal of Architectural Education. I still think it explains quite a bit about architectural fashion, competition, and the peculiar type of architectural pedagogy that results. I’ve put the whole thing online here.

Author Archives: jonochshorn

Milstein’s studio floor

The seventh in my ongoing series of Milstein Hall construction videos is now online:

The index for all my Milstein Hall contruction videos is here.

Milstein Hall, at Cornell University, was designed by Rem Koolhaas and OMA.

stradlater’s roommate

The idea for this new song was triggered by my recent experience signing up with Facebook. Once signed up, I was informed by my younger brother that having only 9 or 10 friends is pretty pathetic. I would periodically check out my Facebook homepage and see that Dan and Eric were now friends, or that Kris and Miki were now friends, which only heightened my sense of insecurity (these thoughts were transcribed into the song’s lyrics in a more-or-less literal way). For the record, Stradlater’s roommate is Holden Caulfield. Lyrics, production notes, and a YouTube video are here.

Also for the record, the video was shot with my low-resolution Flip camcorder and my iMac built-in iSight camera recording simultaneously; the iSight clip is then superimposed onto the desaturated (B&W) Flip clip in Final Cut Express. Various iMac images, some taken by me and others taken from a Google image search, are also interwoven into the video, with the iSight clip always superimposed. Several images taken from the web, appropriately distorted via PhotoShop to match the perspectival conditions they appear in, can be seen every now and then superimposed onto the moving images — the original 45 of Eleanor Rigby rests on the shelf between my speakers; and a copy of Alice in Wonderland or Catcher in the Rye sits on my desk.

Stradlater’s roommate © 2011 Jonathan Ochshorn (remixed Sept. 2, 2019)

VERSE 1:

looking for a friend is tough

do you know of any

nine or ten is not enough

when others have so many

dan and eric are now friends

so are kris and miki

i can’t tell what this portends

maybe i’m too picky

CHORUS 1:

never thought i’d end up like eleanor rigby

wondering what went wrong

waiting at the window screen for someone to pick me

singing where do i belong

VERSE 2:

like alice in the rabbit-hole

in the deep well she falls

mr carroll couldn’t know

that what were wells are now walls

what size do you want to be

the caterpillar asked her

doesn’t matter much to me (she said)

but changing’s a disaster

CHORUS 2:

never thought i’d end up like poor little alice

looking for some fun

everyone she meets is crazy or dripping with malice

and there’s nothing to be done

BRIDGE

i’m not the kind to complain

i’ll take the good with the bad the sun with the rain

but will this rain never end

here it comes again

VERSE 3:

holden’s in a jam again

life sucks what a pity

school’s done so he takes the train

back to new york city

all the women he meets there

leave him sad and lonely

he tells himself he doesn’t care

cause everyone’s a phony

CHORUS 3:

never thought i’d end up like stradlater’s roommate

feeling so alone

finally gets the nerve to call up jane for a new date

but her mom picks up the phone

CHORUS 3 (repeated):

never thought i’d end up like stradlater’s roommate

feeling so alone

hanging it up after calling jane for a new date

when her mom picks up the phone

update on egress and mezzanine in Milstein Hall

Two issues have emerged with the construction of partitions in the crit space of Milstein Hall (Rem Koolhaas, OMA architects), under the concrete dome.

1. In a prior post, I mentioned that the interconnected spaces in Milstein Hall should probably not be permitted under the 2002 Building Code of NYS, since such an open geometry containing an unenclosed egress stair is legal only if no more than two stories are connected. Only if the “first-floor” lobby level is called a mezzanine — so that it becomes part of the lower-level space, reducing the number of stories from three (basement, first, and second) to two (first and second only) — do these interconnected spaces appear to comply with the Code.

However, the definition of a mezzanine has two requirements: it must have no more than one third the area of the room or space it is in; and it must be actually “in” the room or space it is in (the lower level crit space under the dome). I discussed the ambiguity of the requirement for the mezzanine to be “in” the crit space, but also warned that the whole pretense would fall apart if the crit space was subdivided in the future, since in that case, the lobby might no longer qualify as a mezzanine and the openings connecting three stories would clearly not be legal.

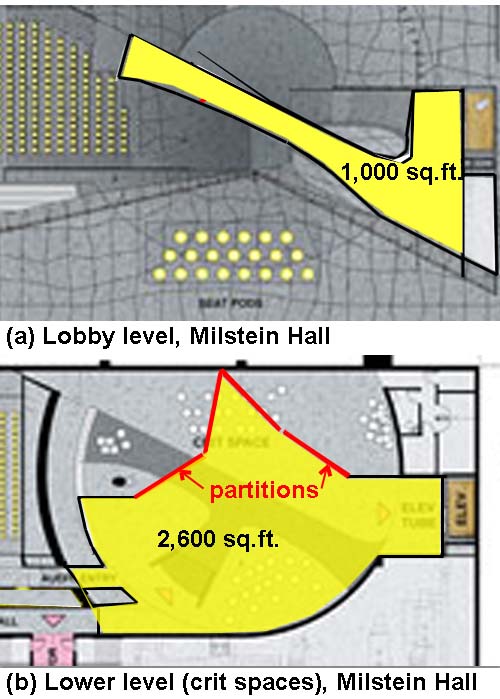

Well, the future is now. Partitions are being finished within the lower-level crit space (see Figure 1) that subdivide the larger space into smaller rooms or spaces. As can be seen in Figure 2, the largest of these newly-subdivided spaces is approximately 2,600 square feet, while the lobby is approximately 1,000 square feet. Since the lobby has an area that is more than one third that of the space below, it no longer qualifies as a mezzanine.

In other words, the lobby must be considered as a separate story, and the openings in what are now three interconnected stories become noncompliant, if they weren’t already.

2. The second issue has to do with required egress from spaces with more than 50 occupants. In a prior post I described the unacceptable location of exits in the crit space, since they are too close to each other to qualify as separate exits under the Code. Now that partitions are being constructed to subdivide the crit space, the same problem occurs in the smaller rooms being created.

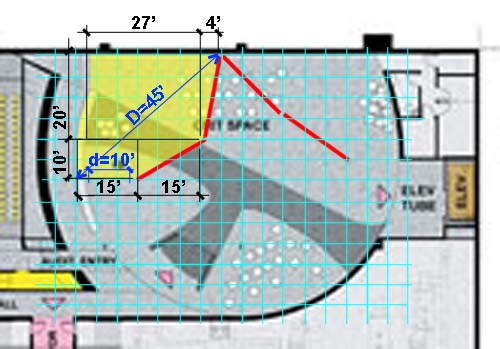

The Code requires that any room with more than 50 occupants have two separate exits, and that these exits be a distance apart no smaller than one third the diagonal length of the room. To determine the number of occupants, one identifies the type of use, in this case an “assembly” occupancy with chairs that are not fixed. For such a use, the Code assigns 7 square feet per occupant. The area of the subdivided room in question, shown with a yellow tone in Figure 3, can be calculated as follows:

27 x 20 = 540 square feet

0.5 x 20 x 4 = 40 square feet

10 x 15 = 150 square feet

0.5 x 10 x 15 = 75 square feet

The total room area = 540 + 40 + 150 + 75 = 805 square feet.

Assuming 7 sq.ft. per occupant, the room must be designed for 805 / 7 = 115 occupants.

Even if the room had tables and chairs, like a classroom with 15 sq.ft. per occupant, it would still need to be be designed for 805 / 15 = 54 occupants.

Using either of these assumptions, two exits are required. The partitions only provide one exit. And this single exit is not wide enough to qualify as two exits based on its length compared to the diagonal length of the room.

The fact that these permanent partitions are movable shouldn’t change any of the conclusions drawn here. They are able to be configured in ways that are sometimes compliant and sometimes noncompliant, but they must be judged based on all possible geometries, especially those that put people and property in danger.

implausible egress interpretation

[Updated below] Aside from limiting the fuel within a given fire area through various compartmentation strategies, a fundamental component of all fire safety requirements is to provide protected paths of escape (egress) for building occupants in the event of a fire incident. The number and characteristics of these so-called means of egress depends on several variables, including the type of occupancy and the number of occupants. The large critique (crit) space under the dome of Milstein Hall (Rem Koolhaas, OMA architects) does not seem to meet these egress requirements.

The number of occupants in the crit space should be taken as the larger of (a) the actual number of anticipated occupants or (b) a number found by dividing the floor area of the space by the tabular floor area per occupant found in Table 1003.2.2.2 of the 2002 Building Code of NYS (Maximum floor area allowances per occupant). Following are the tabular values for assembly spaces — and the crit space certainly seems to count as an A-3 assembly space:

• Chairs only, but not fixed = 7 square feet per occupant

• Standing space = 5 square feet per occupant

• Unconcentrated, i.e., tables and chairs = 15 square feet per occupant

The most generous interpretation for the occupant use of this space would be “chairs, not fixed” with an allowance per occupant of 7 square feet. This corresponds to the reality of such critique assembly spaces, which can be crowded with students and faculty reviewers. Assuming an approximate floor area of 3,600 sq. ft. (the actual area may well be closer to 4,000 sq.ft.), the number of occupants in this space is 3600 / 7 = 514.

For any Group A or B space with 51 or more occupants, at least 2 exits from the space are required. Per Table 1005.2.1, three exits are required for 501-1000 occupants. Therefore, at least two, and possibly three, exits are needed from the crit space. It’s hard to imagine having more than 500 occupants in that space, as there are not that many architecture students in the entire program, but even with less than 500 occupants the requirement for two exits appears, at first glance, not to be met.

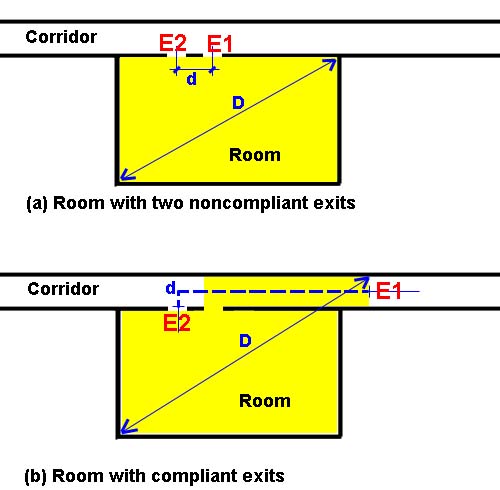

According to Section 1004.2.2.1 of the Code, and assuming that only two exits are needed, these two exits must be “placed a distance apart equal to not less than one half [or one third for this sprinklered space, per exception] of the length of the maximum overall diagonal dimension of the building or area to be served.”

As can be seen in Figure 1a, two exits from a room with more than 50 occupants cannot be placed next to each other, since the distance, d, must be at least one third the length of the diagonal distance, D. But what if we pretend that the room actually extends into the corridor, as shown by the shaded yellow area in Figure 1b? In that case, the two exits are now still not compliant, since even though one of them, E1, has been “moved” far enough away such that the distance, d, is now greater than one third of the distance, D. Nothing has changed to make the room safer, but and the exits are now still not compliant.

Of course, one needs One would need to stretch beyond plausibility the definition of a corridor to make this work. A corridor is a type of exit access, which the Code defines as follows: “That portion of a means of egress system that leads from any occupied point in a building or structure to an exit.” It seems clear that the corridor shown in Figure 1 really is acting as a corridor, and not as a part of the room. But the main point is this: even if the corridor is envisioned as “part” of the room, the egress situation remains noncompliant, because the occupants of the space still need to pass through what amounts to a single exit, rather than having two exits available. [see update 3 below] But how does this apply to the crit space in Milstein Hall?

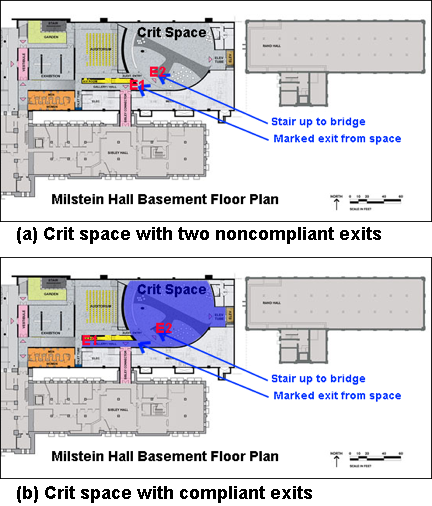

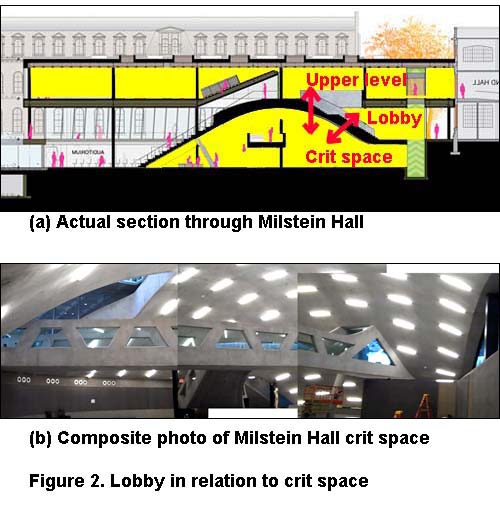

If the second exit from the crit space is assumed to consist of the unenclosed stair leading to the bridge above the crit room space, this second exit (marked E2 in Figure 2) does not appear to conform to the requirement that it be a minimum distance from the first exit (marked E1) — this distance determined by dividing the maximum diagonal length of the room by three.

To solve this problem, the architects for Milstein Hall have attempted to use used the trick outlined above: as explained to me by Cornell’s Project Director for Milstein Hall, the crit space actually extends into what appears to be the corridor leading to the exit (see Figure 2b with the extent of the crit space shown in blue). In fact, there are even felt pin-up walls in this “corridor” to lend credence to this interpretation. Even so, the safety of the crit space appears to have been compromised by this imaginative Code interpretation.

[Update: Oct. 13, 2011] As I describe in a later post, the smaller crit spaces formed by new partitions also have egress problems.

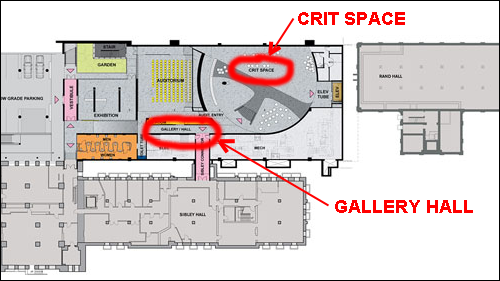

[Update 2: Oct. 13, 2011] One might have more sympathy for the architects’ contention that the crit space actually extends into the corridor if they had indicated this intention on their plans. In fact, they label the corridor separately from the crit space (calling it a “gallery/ hall”) as can be seen in this annotated screen shot taken from Cornell’s Milstein Hall website:

[Update 3: March 1, 2012] The deleted text and bold-face additions above are intended to clarify the point that I was trying to make: that the crit space under the dome in Milstein Hall (or any similarly configured space with more than 49 occupants) is noncompliant with egress regulations in building codes. This judgment was recently supported by a Code expert from the International Code Commission (which publishes the International Building Code upon which the New York State Building Code is based); I will publish his written opinion as soon as I receive it [the Code opinion can be found here].

milstein hall and its interconnected spaces

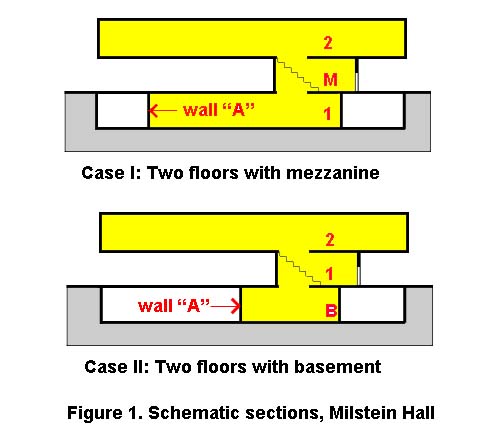

Milstein Hall at Cornell (Rem Koolhaas, OMA architects) contains what appears to be three floors, all interconnected with an opening through which passes an unenclosed egress stair. Such a condition, unless it is designed as an atrium with special smoke control measures, would not be permitted under the New York State Building Code — see my discussion of holes in floors.

Milstein Hall's interconnected spaces -- crit space below, lobby/bridge in the middle, and studios above -- can be seen in this image

I asked the Project Director for Milstein Hall how such an interconnected opening was possible, since the interconnected spaces were clearly not designed as an atrium. He explained that, contrary to appearances, the building only has two stories with no basement: what appears as the basement is actually the first floor; what appears as the first floor is actually a mezzanine; and only the second floor is really what it appears to be — the second floor. Mezzanines need to be no more than one-third the floor area of the room or space they are in, and the first-floor lobby of Milstein did appear to be no bigger than one-third the floor area of the crit space under the dome to which it is connected.

However, while the interconnected openings in Milstein Hall appear at first glance to meet the “letter” of the Building Code, they may well be noncompliant.

Comparing Case I and Case II in Figure 1, one can see that the entire rationale for allowing an unenclosed egress stair from the second floor to the mezzanine lobby depends on the relative area of the space defined by what I have schematically called wall “A.” If wall “A” is placed in such a way that the area of the space it forms is at least 3 times bigger than that of the lobby (Case I), then the lobby can be counted as a mezzanine, and the egress stair is then technically within an unenclosed opening connecting only two stories, thereby conforming with exception 8 or exception 9 in Section 1005.3.2 of the 2002 New York State Building Code.

However, if wall “A” is moved so that the area of the space it forms is less than 3 times the size of the lobby (case II), then the lobby cannot be called a mezzanine. It now becomes the first floor, and the same openings and egress stair become noncompliant.

This seems entirely irrational, since Case II, with less floor area to house combustible products and a smaller number of occupants than Case I, is nevertheless noncompliant, whereas Case I, with a larger area and therefore more occupants and potentially combustible products, would be deemed compliant.

It seems probable either that the writers of the Code never anticipated that their definition of mezzanine would be exploited in this way, or that other aspects of the mezzanine definition make this geometry noncompliant.

The definition of mezzanine, found in Section 502 of the 2002 Code, states that it must have “a floor area of not more than one-third of the area of the room or space in which the level or levels are located.” The key word here is “in.” The mezzanine must be “in” the room or space, not outside the room or space with an opening that connects them. Now, one might debate what exactly the meaning of the word “in” is (by analogy to Bill Clinton insisting that a proper interpretation of his prior testimony “depends on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is”). As can be seen in Figure 2, common sense would suggest that the lobby is not “in” the dome. Both the section (Figure 2a) and the composite photo (Figure 2b) show clearly that the concrete structure of the dome creates a distinct “room” or “space” and that the lobby (pictured through the hole in the dome visible at the left of Figure 2b) is completely outside that space.

It is possible (along the lines advocated by Clinton) to define “in” topologically rather than by recourse to “common sense”; in that case the lobby can indeed be tested as a mezzanine “within” the dome “crit space.” In other words, we could draw a continuous contour line through the opening connecting the two spaces and call the resultant figure a single space. But the Code is fairly careful about the prepositions it deploys. If the intent were to allow a mezzanine to have any interconnected relationship to a room or space, other words or phrases could have been chosen instead of “in” or “within.” The Code does not describe a mezzanine as being “next to” or “adjacent to” or “connected to” some other room or space: it specifically says that a mezzanine must be “within” a room.

Still, this is admittedly ambiguous. The commentary to the 2009 IBC doesn’t really help: “So as not to contribute significantly to a building’s inherent fire hazard, a mezzanine is restricted to a maximum of one-third of the area of the room with which it shares a common atmosphere.” Here, the phrase “common atmosphere” has two purposes: first, it signals that the mezzanine must be somehow contiguous with the space it is in; second, it excludes any “enclosed portion of a room” in computing “the floor area of the room in which the mezzanine is located.” Having a “common atmosphere” appears therefore to be a necessary, but not sufficient condition. The mezzanine must also be “in” the room or space, which again brings us back to the question of what “in” is.

But this much is true: if the lobby space cannot be called a mezzanine, then it counts as a story. In that case, the interconnected openings are noncompliant, as they meet none of the exceptions for shaft enclosures outlined in Section 707.2 of the 2002 Code. And even if the lobby is now granted the status of mezzanine, the crit space under the dome becomes locked into its current geometry forever: it can never be reconfigured, for example, into a series of smaller rooms, since the lobby would then exceed its maximum floor area qua mezzanine and would revert back to being a separate story. The opening connecting what would now be three interconnected stories would be noncompliant.

[Update: Oct. 13, 2011] As I describe in a later post, the crit space has now been subdivided into a series of smaller rooms, appearing to make both the lobby noncompliant as a mezzanine, and the interconnected stories with an unenclosed egress stair noncompliant according to the various allowable exceptions for shaft enclosures.

problems with the third-floor exterior wall of East Sibley Hall

[updated below Oct. 13, 2011 and March 9, 2012] Appendix K of the 2002 New York State Building Code made significant changes to the model 2000 International Building Code (IBC) upon which the New York State Code was based. It allowed a building addition to “increase the area of an existing buiding beyond that permitted under the applicable provisions of Chapter 5 of the Building Code for new buildings” as long as a fire barrier was provided.

Normally, a fire wall — not a fire barrier — would be required in such cases, but NYS legislators wanted to make it easier and less expensive (and therefore less safe) to build additions to existing structures. Whereas it is absolutely clear what a fire wall is, and where it must be placed in relation to the parts of a building it is separating, this hastily contrived NYS appendix doesn’t bother to specify exactly where its alternative fire barrier must be provided.

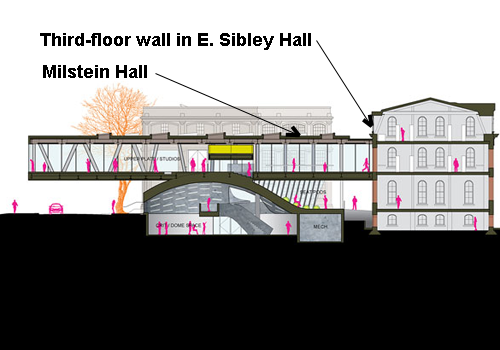

This wouldn’t be much of a problem if the addition were the same height as the existing building. However, Milstein Hall at Cornell University (OMA – Rem Koolhaas architects) is a two-story building addition connected to Sibley Hall, which is a three-story building (see building section below, adapted from Cornell’s Milstein Hall web site). The architects for Milstein initially had called for a fire barrier between the two buildings, but only on the second-floor where they literally connect. It was only later, when this assumption was challenged, that they added fire barrier protection at all levels where the two buildings come into contact (i.e., at the basement and first-floor levels as well) — see update below. Left with no protection at all is the thrid-floor exterior wall of E. Sibley Hall overlooking Milstein’s green roof.

This is a problem for two reasons. First, the window openings on the third floor of Sibley have no fire protection. Second, the wooden load-bearing exterior wall of Sibley’s third floor has no fire-resistance rating. None of this was a problem when Sibley was a non-conforming, grandfathered, free-standing building. It becomes a problem with the construction of Milstein Hall.

The 2002 New York State Code (specifically, Section 704.10), under which Milstein was permitted, requires that “opening protectives” be provided “in every opening that is less than 15 feet (4572 mm) vertically above the roof of an adjoining building or adjacent structure that is within a horizontal fire separation distance of 15 feet (4572 mm) of the wall in which the opening is located.” All of the window openings in the third floor of E. Sibley Hall that overlook Milstein Hall qualify under this section for opening protectives. The only exception to this requirement is where the roof construction below the openings has a 1-hour fire-resistance rating and its structure (i.e., the steel beams and girders supporting the roof) has a 1-hour fire-resistance rating. Milstein’s roof structure has no fire-resistance rating, so the exception does not apply.

Not only do Sibley’s third-floor windows require opening protectives, but the entire exterior wall on the third floor of Sibley (facing Milstein Hall) needs to be reconstructed with a 1-hour fire-resistance rating. Footnote “f” in Table 601 (exterior bearing walls) requires that the fire-resistance rating of the wall be not less than that based on fire separation distance (Table 602). Table 602 requires a 1-hour fire-resistance rating for Occupancy Groups A or B if the fire separation distance is less than 5 feet.

The fire separation distance between Sibley and Milstein Halls is 0 feet (they are physically connected), based on the most generous assumption that one can make, i.e., that they are effectively two separate buildings. Actually, Appendix K only allows them to be considered as separate buildings from the standpoint of “area” (K902.2). However, if they were considered as a single building — as would be required under the current building code (i.e., without a fire wall) — then all of this discussion would be moot since Milstein Hall would be clearly noncompliant. Either way one looks at it — as a single building or as two separated buildings — the current situation appears to be noncompliant.

[Update: Oct. 13, 2011] As it turns out, the nonconforming fire barrier placed between Sibley and Milstein Hall — to satisfy the ambiguous requirements of Appendix K from the 2002 Building Code of NYS — is not only nonconforming but also noncompliant. The width of fire-rated openings in such a fire barrier cannot exceed 25 percent of the length of the fire barrier wall. In the image below, the aggregate width of openings is shown graphically in relation to the total length of the fire barrier wall. It can be seen that the opening width greatly exceeds the 25 percent limit:

[Update: March 9, 2012] A noncompliant solution to the fire barrier problem was proposed and recently installed. At great expense. And completely useless. See my analysis here.

cornell’s fine arts library in Rand Hall

There are plans to move Cornell’s Fine Arts Library from Sibley Hall, where it has existed as a nonconforming (”grandfathered”) occupancy for quite a few years, to Rand Hall, which is now connected to Sibley Hall through newly-constructed Milstein Hall. Because the addition of Milstein Hall was, and is, nonconforming with respect to the current New York State Building Code, it may not be possible to put a library occupancy in Rand Hall. I made a similar argument about placing so-called Group A occupancies in Sibley Hall. This same explanation applies to Group A occupancies in Rand.

A future change to an A-3 (library or lecture hall) occupancy in Rand Hall should not be permitted, because such a change would be replacing an existing occupancy with one of a higher hazard. The relevant code language is as follows: Section 812.4.2.1 of the Existing Building Code of New York State says: “When a change of occupancy group is made to a higher hazard category as shown in Table 812.4.2, heights and areas of buildings and structures shall comply with the requirements of Chapter 5 of the Building Code of New York State for the new occupancy group.” Table 812.4.2 classifies group A-3 spaces as having a “relative hazard” of 2 (with 1 being the highest hazard), and group B spaces (the current occupation of Rand’s 2nd and 3rd floor, per email from City of Ithaca Senior Code Inspector John Shipe) as having a relative hazard of 4 (lowest hazard). Therefore, it is clear that a change from group B to group A-3 constitutes an alteration to a higher hazard occupancy.

With such a change, the building — which under the current building code is defined as Rand-Sibley-Milstein — must conform to the requirements of Chapter 5 of the current Building Code of New York State. What are those requirements? Chapter 5 regulates the allowable heights and areas of buildings, based on construction type and occupancy. Since the fire barrier separating Milstein and Sibley Halls is nonconforming with respect to the current code, it [i.e., the fire barrier — clarification added 10/2/11] cannot be invoked to consider Rand-Milstein Hall as a separate building, as would be the case with a fire wall. Therefore, Rand-Sibley-Milstein must be treated as a single building under the current code, and the height/area limits are as follows: the maximum height is 60 feet; the maximum number of stories is two; and the maximum area on a single floor is at most 22,500 sq.ft. The combined second-floor area for Rand-Sibley-Milstein greatly exceeds this limit of 22,500 sq.ft., and the number of stories in Rand-Sibley-Milstein similarly exceeds the Code limit of two. Based on either of these criteria (floor area or number of stories), any alteration to a higher hazard occupancy should not be permitted, as the requirements of Chapter 5 would not be met, and cannot be met.

In other words, putting the library on the 3rd floor of Rand would violate the Code limit of two stories; putting the library on the 2nd floor of Rand would violate the floor area limit.

[Update: Oct. 13, 2011] The move of the Fine Arts Library into Rand Hall has taken place this past week, in spite of the objections I have raised. Here are a few additional points, for the record:

1. On Oct. 7, 2011, I sent an email to the Milstein Hall project director which included this clarification:

“I didn’t mention this to GW at today’s meeting, but my notes that I gave him on Code issues (attached) state that: ‘the exception [to Section 912.5.1 of the Existing Building Code of NYS] only permits a fire barrier, if used in lieu of a fire wall, to meet area limitations for the new occupancy — NOT height limitations. Only a fire wall can meet both height and area limitations for the new occupancy.’ In other words, the library move to the 3rd floor of Rand will not be in compliance even if the fire barrier between Rand and Milstein is upgraded. Only a fire wall would make such a move compliant. On the other hand, an upgraded fire barrier would appear to allow such a move to the second floor of Rand Hall. In either case, the current fire barrier is noncompliant.”

2. The contention that a library (A-3 occupancy) constitutes a higher hazard occupancy compared to the current use in the Rand Hall space is the underlying reason why such a move is noncompliant. The Code is unambiguous about the occupancy of libraries as A-3. Design studios are not specifically mentioned in the Code; rather, they fall under the Group B definition for educational occupancies above the 12th grade. If there was any doubt about the legitimacy of this classification, the Ithaca Building Department files for Rand Hall contain numerous documents, all confirming that the Group B designation was actually used for the studio spaces in Rand Hall. Older documents in the file show a C5.5 designation; this was the old New York State Code subcategory for Educational occupancies within the “Commercial” category — exactly equivalent to the modern Group B designation. See this document copied from the Rand Hall Building Department file.

3. Even if a fire wall were built between Rand and Milstein Halls, it would still be necessary to upgrade the two egress stairs in Rand Hall, which are noncompliant once the occupancy on the third floor changes to a higher hazard. For details, see my email to the Milstein Hall project director.

graduation day

I got the idea for this song after being called upon to read the names of graduating students at Cornell’s architecture department commencement ceremony out on the Arts Quad May 29, 2011. The YouTube video is here. Remixed Sept. 1, 2019. By coincidence, an article about J.D. Salinger’s distaste for graduation ceremonies appeared in the NY Times on the same day that I uploaded the video. Salinger is quoted as saying: “I’ve been going to graduations, and there isn’t much that I find more pretentious or irksome than the sight of ‘faculty’ and graduates in their academic get-ups.” The Times reporter added that Salinger apparently needed all his self-control “not to gag.”

The video borrows short pieces of Bill Clinton’s honorary degree speech at the NYU commencement that was held at Yankee Stadium in 2011. However, the lyrics that I wrote about “spouting every known cliché” apply to all commencement speeches ever spoken, and are not directed specifically at Clinton’s abundant catalog of clichés, although — as they say — the shoe fits.

[updated 7/5/11] I just received this photo of the Cornell Architecture event which inspired the song:

you baby

You Baby is a new song, recorded May 2011. Watch the YouTube video. Actually, I wrote the music for this song many years ago, probably in the early or mid 1980s. It was only recently that I decided to add words, a task that was rather complicated because the original music was never intended as a “song.” The lyrics themselves are rather strange, as they at first appear to be of the conventional “I love you” type, but upon closer scrutiny reveal, if not exactly an opposite sensibility, then at least a kind of resignation about the more-or-less arbitrariness of the whole concept.

This is the first video that features my entire band: Jonathan on electric guitar, Jonathan on drums, Jonathan on electric piano, and some other guy on bass (I’m actually playing bass as well, but don’t own an instrument that can be photographed). So the bass player was borrowed from some other video where he was introducing guitarist Laurindo Almeida playing with the Modern Jazz Quartet. Through the magic of Photoshop and Final Cut Express, I convinced him that he was not just a host, but a musician in his own right.

For those of you curious about the video itself, this is basically how it was produced: all the individual clips of Jonathan playing the various instruments are shot with a low-resolution Flip Camcorder, placed either on a tripod or hand-held (e.g., where I’m holding the camera with my left hand while playing the keyboard with my right hand). These individual clips are then inserted behind an image of a suitable band, in this case taken from some Steely Dan concert.

Original image of Steely Dan concert (left); modified image with band members removed leaving transparent background, shown here in red (right).

I shoot most of the clips in front of a piece of black fabric, so that they blend into the (default) black background behind the transparent spaces. It takes a bit of color correction to match them up, but it’s a lot easier than using the Chroma Key feature. The only other tricks are putting the bass player’s arm and his instrument on separate tracks so that they can be moved a bit using Final Cut’s motion keyframe features. I temporarily imported a GarageBand version of just the “slapped” bass line into the Final Cut “timeline,” so I could easily match the arm movements with the actual music being played (the original GarageBand score has a conventional bass track in addition to the “slapped” bass track).