Following is a transcription of an email that I wrote to the Dean of the College of Art, Architecture, & Planning at Cornell University on Sept. 6, 2010 (copied to the Assistant Dean for Administration, AA&P; the Project Director for Milstein Hall; and the Building Commissioner and Deputy Building Commissioner of the City of Ithaca) [9/10/10 updates below]:

Portions of East Sibley and Rand Halls are in serious danger of being noncompliant with the NYS Building Code, and their ability to remain occupied for library, studio/classroom, and office use may be in jeopardy.

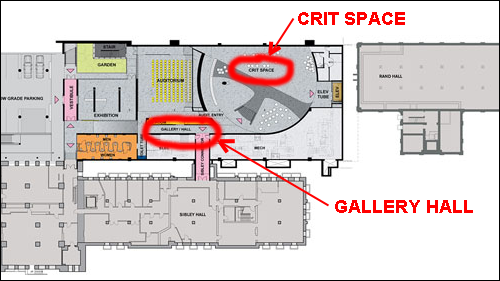

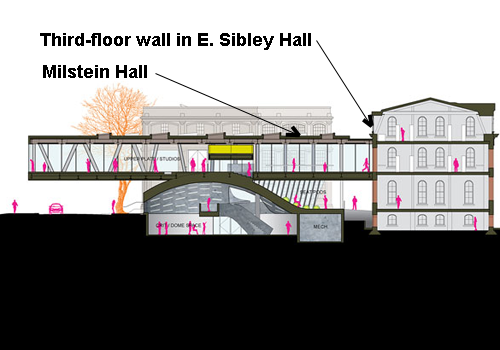

Once the floor/roof structure of Milstein Hall is in place, two things immediately occur that threaten the continued occupation of the adjacent, connected buildings.

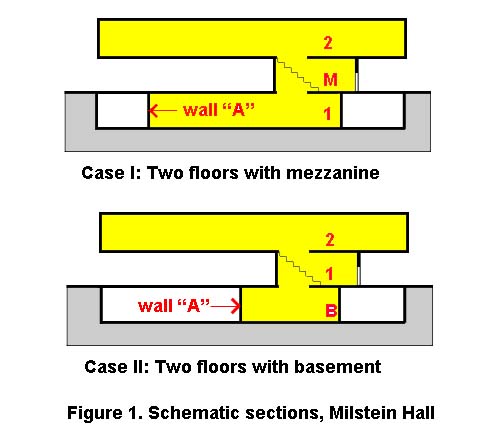

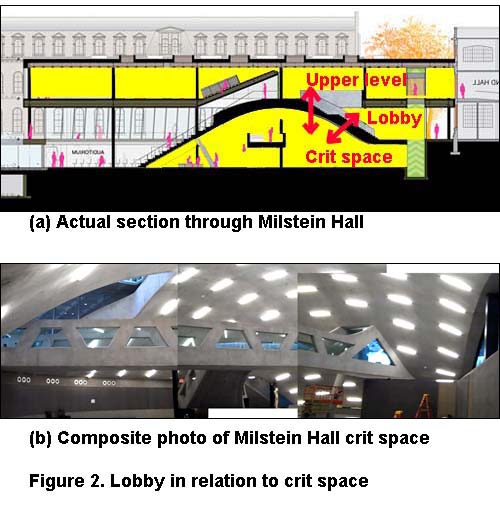

First, all covered space under the structure of Milstein Hall counts as building area for Sibley Hall whether or not those spaces are enclosed, since a fire barrier is not yet in place to separate the two structures. Under these current circumstances, East Sibley Hall contains floors whose areas — that is, the combined, unseparated, floor areas of East Sibley and Milstein Halls — exceed that allowed by the Code, given the limits imposed by the governing V-B construction type for Sibley Hall.

Second, once the floor/roof structure of Milstein Hall is in place, the windows in Sibley Hall under these covered spaces no longer function as openable windows for the purpose of natural ventilation. I understand that Cornell and City of Ithaca Code Enforcement officials have challenged this contention, but I must insist that it remains true. As I pointed out previously, the Code limits natural ventilation to windows opening to “yards” or “courts.” Yards and courts must be “uncovered space, unobstructed to the sky” (see chapter 2 definitions in the Code). The Code does not permit windows used for natural ventilation to open into any other type of spatial geometry, whether or not “outdoor air” can somehow work its way to the window opening. The Commentary to the Code (written for the International Building Code, or IBC, from which the NYS Code derives) is absolutely unambiguous: “In order that adequate air movement will be provided through openings to naturally ventilated rooms, the openings must directly connect to yards or courts with the minimum dimensions specified in Section 1206” (Commentary for Section 1203.4.3 Openings on yards or courts). Since the openings “must directly connect to yards or courts” and since yards and courts must be “uncovered space, unobstructed to the sky,” the East Sibley windows at or below the second-floor of Milstein do not provide natural ventilation. Without mechanical ventilation that meets the criteria specified in the New York State Mechanical Code, the rooms are noncompliant and should not be occupied. In prior emails, I have outlined why the ad hoc provision of room air conditioner units or fans does not satisfy the requirements of the Mechanical Code. Yet aside from such rooms, it is clear that classrooms (e.g., 142-144 ES) or library spaces (e.g., the entire second-floor F.A.L. In E. Sibley) that have absolutely no mechanical ventilation will certainly not meet those Code requirements.

The second floor of Rand Hall, due to changes in the window configuration that have reduced the openable area, also has problems meeting Code criteria for natural ventilation. The current second-floor studio area (field measurements taken 9/3/10, excluding enclosed computer rooms, etc.) encompasses 5,259 square feet. The required vent area from openable windows is 4% of 5,259, or 210.4 square feet. However, the actual available vent area from openable windows, equal to 15 windows times 11.625 square feet of vent area per window, is only 174.4 square feet total. This is clearly noncompliant, and yet no mechanical ventilation is being planned for the studio space [see prior comments].

It is not my intention to speculate as to why East Sibley Hall and the second floor of Rand Hall are being occupied in spite of these apparent Code violations (lack of required ventilation in Rand and East Sibley Halls; and lack of fire barrier protection in East Sibley Hall). But whatever the reasons, the problems need to be addressed. It seems to me that either the noncompliant spaces should be vacated until Sibley/Milstein/Rand Hall is completed, or the twin problems of ventilation and fire protection should be corrected immediately.

Update 1 (9/10/10):

Two passages from NFPA 241: Standard for Safeguarding Construction, Alteration, and Demolition Operations (1996 version quoted here) support my argument about the immediate need for a fire barrier (the NFPA standard mentions “fire wall,” but the same logic applies to a “fire barrier” used as a substitute for a fire wall) between Sibley Hall and Milstein Hall:

1-1.1

Fires during construction, alteration, or demolition operations are an ever-present threat. The fire potential is inherently greater during these operations than in the completed structure due to previous occupancy hazard and the presence of large quantities of combustible materials and debris, together with such ignition sources as temporary heating devices, cutting/welding/plumber’s torch operations, open fires, and smoking. The threat of arson is also greater during construction and demolition operations due to the availability of combustible materials on-site and the open access.

6-6 Fire Cutoffs.

Fire walls and exit stairways, where required for the completed building, shall be given construction priority for installation… [and yes, the fire barrier is required for the completed building].

Update 2 (9/10/10):

I want to clarify that both of the actions I am recommending (mechanical ventilation for E. Sibley Hall rooms adjacent to Milstein Hall; and installation of a fire barrier in all E. Sibley Hall windows adjacent to Milstein Hall) are already part of the Milstein Hall scope of work. The issue is not whether they are required — they are both required and included in the Milstein Hall budget — but whether E. Sibley Hall can remain occupied during construction without these two items being put into place. In my view, the Code is clear on both issues: E. Sibley Hall should not remain occupied without adequate provision for ventilation and fire protection.

Furthermore, since both of these items are already part of the Milstein Hall scope of work, it is absolutely incomprehensible why the project’s phasing plan did not prioritize these two items so that E. Sibley Hall could remain safely occupied during construction. Well, actually, it is not so incomprehensible: the initial plans and specifications submitted to the City of Ithaca Building Department for a building permit included neither a proper fire barrier nor adequate mechanical ventilation for Sibley Hall. It was only after I raised objections through the FEIS comment process that the architects for Milstein Hall extended their fire barrier to the first and basement floors of Sibley Hall, and accepted the need for mechanical ventilation in Sibley Hall (after deciding to put fixed fire-rated glazing in all E. Sibley windows adjacent to Milstein). These architects still have not admitted that natural ventilation from windows under Milstein Hall is no longer a possibility given Code requirements for “yards” and “courts” adjacent to all windows used for natural ventilation; and continue to maintain that it is only because of the fixed glazing required for their fire barrier design that mechanical ventilation becomes necessary.