A new chapter has been added to my critique of Milstein Hall, designed by OMA/Rem Koolhaas, at Cornell. This one deals with fire safety.

Category Archives: Milstein-Rand-Sibley Hall

Critique of Milstein Hall

I’m working on a critique of Milstein Hall at Cornell University, a new building designed by Rem Koolhaas (OMA) and completed in 2011-2012. Ultimately, the critique will encompass various issues that can be discussed objectively: sustainability, fire safety, nonstructural failure, function, and flexibility. At this point, only the first piece on sustainability is online. Other “chapters” will eventually be linked from the same site.

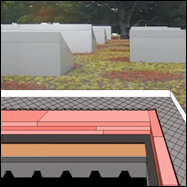

Milstein Hall’s green roof video

new Milstein Hall construction videos

I’ve just posted two new Milstein Hall construction videos (Nos. 8 and 9), describing the curtain wall, stone veneer, and aluminum soffit panels. Milstein Hall at Cornell University was designed by Rem Koolhaas/OMA. The index for all my Milstein Hall construction videos is here. The two new ones can be viewed below:

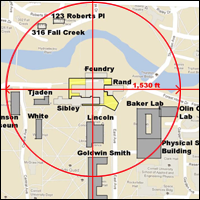

Milstein Hall’s noncompliant fire barrier

Last September, 2011, I requested a meeting with Mike Niechwiadowicz, Deputy Building Commissioner for the City of Ithaca, to discuss, among other things, the inadequate fire barrier between Milstein Hall (designed by Rem Koolhaas and OMA) and Sibley Hall at Cornell University. This fire barrier, already providing less fire protection than what would normally be required, was itself incorrectly specified when a building permit was requested in 2006, under the old NY State Building Code that was about to expire.

Changes were made after the permit was issued, so that the fire barrier was extended from the second floor — where it was originally called for — to the basement and first floor of Sibley Hall. This fire barrier consisted of the existing masonry wall of Sibley, plus fixed panels of 3/4 hour fire-resistance rated glazing or fire-rated glass doors installed in all the window openings that faced Milstein Hall.

Unfortunately, as I pointed out to Cornell’s Project Director for Milstein Hall as well as Deputy Building Commissioner Niechwiadowicz on September 9, 2011, the fire barrier still was noncompliant, as it contained too great a width of openings in the masonry wall, even with their fixed panels of rated glass.

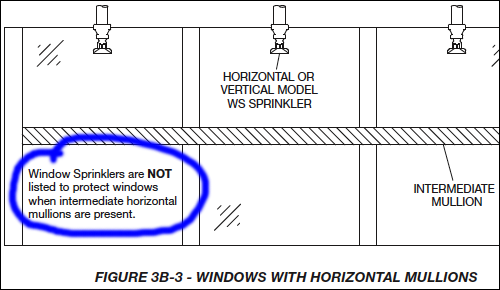

On October 21, 2011, I met with Cornell Project Director Gary Wilhelm, at the suggestion of Mike N., who then sent me his proposed “solution” to the fire barrier problem: to install special sprinklers on enough of the offending glass panels that the maximum width limit would not be exceeded. This special system developed by Tyco Fire Products essentially allows the window openings to count as fire-resistance rated walls. I examined the specifications for this product and found that they were inappropriate for the intended application, because they cannot be used where the rated glazing has any horizontal mullions — and the glazing installed in the Milstein fire barrier has horizontal mullions.

So, I relayed this information to all concerned on October 21, 2011, and didn’t hear anything else about the system until it was actually installed just a few weeks ago.

Well, perhaps I was mistaken about the appropriateness of such sprinklers in this application. Today, I called Tyco and spoke to a technical representative. Not only did he confirm that the system cannot be used where horizontal mullions are present, but he said that the application that I described was completely useless because one half of the sprinklers were sandwiched between the fire-rated glazing and the existing windows of Sibley Hall. Since the sprinklers, to be effective, must be in contact with the heat of the fire, placing a barrier like an ordinary window between a potential fire and the sprinklers renders them nonfunctional and therefore noncompliant.

more on implausible egress in Milstein and Sibley Halls

[Updated below: updates #2, #3, #4, and #5 below] Here is the text of an email that I sent to Dean Kent Kleinman (College of Architecture, Art, and Planning, Cornell University; copied to numerous other relevant parties) dated March 5, 2012. I have written previously about the Milstein dome crit space egress problem here.

I am concerned that events are being planned “under the Milstein Hall dome” and in other spaces in Sibley Hall that may involve more than 49 occupants… Two exits separated by a minimum Code-specified distance are required in such cases, and neither the Milstein dome crit space nor room 261 E. Sibley Hall meet those standards. I have already raised this concern about the Milstein dome with Gary Wilhelm and Peter Turner (email dated 9/30/11, copied to Mike Niechwiadowicz) and about 261 ES with Rich Jaenson (email dated 2/20/12). Wilhelm explained to me that a second remote exit from the dome crit space is actually further down the corridor outside the dome itself — an explanation that does not satisfy the egress requirements for fire safety in the NY State Building Code (Wilhelm’s interpretation is explicitly contradicted by a “technical opinion” requested from the International Code Council which I have attached [see below]; this opinion strongly confirms my judgment that the dome space cannot legally support occupation by more than 49 people; the same logic applies to 261 ES if a second marked and non-lockable exit is not provided).

Cornell has already lost a court case concerning spaces with only one exit that are used for occupancies greater than 49 people (this case concerned, among other rooms on campus, 157 E. Sibley Hall; for details, see here).

In the case of room 261 E. Sibley Hall, posted occupancy signs permit from 112 to 300 people in the space even though two remote exits are not provided. I am not clear whether a building permit was obtained for this change of occupancy from the old Fine Arts Library stacks (with a Code-sanctioned occupancy of approximately 15 people) to a space for 300 people, but recent experience has shown that even building department review does not guarantee Code compliance.

Cornell, through the ILR school, maintains an excellent web site devoted to the Triangle Factory Fire of March 25, 1911 (here), a disaster that was caused, in part, by a cynical and dangerous attitude toward egress. One would think that over 100 years later, the lessons of that tragedy would resonate more clearly in the actions taken within the architecture school.

Jonathan Ochshorn

Email from Michael W. Giachetti, P.E. to Jonathan Ochshorn received March 5, 2012, based on Ochshorn’s description of the conditions in the Milstein dome crit space, as illustrated in his blog post dated Oct. 11, 2011.

Mr. Ochshorn:

Section 1015.2.1 requires the exit doors or exit access doorways to be placed a distance apart equal to not less than one-half of the length of the maximum overall diagonal dimension of the area to be served or one-third the length if the building is sprinklered. In applying the provisions of this section, it is important to recognize any convergence of egress paths that may exist. While the actual exit doors or exit access doorways may be remote, if the paths either before or after these doors converge, then remoteness would not be satisfied. In your example, including the area of the corridor as part of the “room” does not change the fact that the two paths into the corridor are not remote. As such, including the area of the corridor as part of the “room” does not resolve the problem with remoteness.

Code opinions issued by ICC staff are based on ICC published codes and do not include local, state or federal codes, policies or amendments. This opinion is based on the information which you have provided. We have made no independent effort to verify the accuracy of this information nor have we conducted a review beyond the scope of your question. This opinion does not imply approval of an equivalency, specific product, specific design, or specific installation and cannot be published in any form implying such approval by the International Code Council. As this opinion is only advisory, the final decision is the responsibility of the designated authority charged with the administration and enforcement of this code.

Sincerely,

Michael W. Giachetti, P.E.

Senior Staff Engineer

ICC – Chicago District Office

www.iccsafe.org

[Update: March 7, 2012] Dean Kleinman responded to my email yesterday, stating that “the university and the City of Ithaca building officials, copied on this message, have come to a different conclusion and I have confidence in their competency.” As usual, I was given no explanation — just an assurance that the Dean is confident in the “competency” of the various officials charged with making such determinations. I sent a request for an explanation to the City of Ithaca Building Department today, also copied to Dean Kleinman and numerous other relevant parties. The text of this email is as follows:

TO: Mike Niechwiadowicz, City of Ithaca Building Department

Mike,

Please let me know the basis for your conclusion that the “crit space” under the Milstein Hall dome can be occupied by more than 50 persons, even though the actual exits from the space do not comply with Section 1004.2.2.1 of the 2002 NY State Building Code (Two exit or exit access doorways). Do you accept Gary Wilhelm’s explanation that two non-compliant exits (non-compliant because they are too close together) can be made compliant by changing nothing about the actual exit geometry, but by merely labeling one of the two exits as being further down the corridor?

If so, how do you reconcile that judgment with the opinion of the Senior Staff Engineer, ICC, which I attached to the email sent yesterday, and reproduce here: “Section 1015.2.1 [of the 2006 IBC, equivalent to Section 1004.2.2.1 of the 2002 NYS Code] requires the exit doors or exit access doorways to be placed a distance apart equal to not less than one-half of the length of the maximum overall diagonal dimension of the area to be served or one-third the length if the building is sprinklered. In applying the provisions of this section, it is important to recognize any convergence of egress paths that may exist. While the actual exit doors or exit access doorways may be remote, if the paths either before or after these doors converge, then remoteness would not be satisfied. In your example, including the area of the corridor as part of the ‘room’ does not change the fact that the two paths into the corridor are not remote. As such, including the area of the corridor as part of the ‘room’ does not resolve the problem with remoteness.”

If you do not accept Gary Wilhelm’s explanation, then what is the basis for your conclusion?

Note that more than 500 persons are likely to converge on this “crit” space Friday and Saturday nights this week at the invitation of the College of Architecture, Art, and Planning. Any assembly occupancy with “standing space” (as this crit space is configured, see Table 1003.2.2.2 of the 2002 NYS Code) must actually have three exits rather than just two if it is large enough to accommodate 501 or more people (which this crit space is, having more than 2505 square feet of floor area, and assuming 5 square feet per occupant per Code instructions). Thus, you seem to be permitting this space to be occupied with only a single legal exit even though three exits are actually required.

Please explain.

———————

[Update #2: March 8, 2012] I received a reply and explanation from the City of Ithaca Building Department on March 7, 2012 which I copy below, followed by my March 8, 2012 response.

Jonathan,

2003 Building Code of NYS Section 1004.2.5 (equivalent in 2010 Building Code of NYS Section 1014.3) ‘Common path of egress travel’ allows a 75 foot common path of travel before access to two exits is required. The definition of ‘common path of egress travel’ is in Section 1002. Basically, for up to 75 feet only one path to the two exits is required. The Crit space meets this requirement; therefore, it does have two code compliant exits.

Occupancy of the space is limited to 349 because there are only two exits.

Take care,

MikeMichael Niechwiadowicz

Deputy Building Commissioner

City of Ithaca Building Department

108 East Green Street

Ithaca, New York 14850

———————

My email response, dated March 8, 2012, follows (also copied to Dean Kleinman at Cornell and numerous others):

Mike,

Thanks for your prompt response to my questions. I am happy to see that you have rejected the argument advanced by Gary Wilhelm. Unfortunately, the argument you employ to justify having two noncompliant exits in a space with more than 50 occupants (actually more than 500 potential occupants) is equally dangerous and specious. Needless to say, I strongly disagree with your conclusions.

1. The Code is quite clear that the requirement in Section 1004.2.2.1 of the 2002 NYS Code (equivalent to Section 1015.2.1 of the 2009 IBC) for two remote exits from spaces with 50 or more occupants is in addition to the maximum common path of travel limit specified in NYS Code Section 1004.2.5 (equivalent to 2009 IBC 1014.3). Both requirements must be met.

There is no exception under Section 1004.2.2.1 of the 2002 NYS Code (equivalent to Section 1015.2.1 of the 2009 IBC) for situations where the common path of travel limit is satisfied. The common path of travel limit is a separate regulation that must also be satisfied. Satisfying this limit for common path of travel does not give you permission to violate other provisions of the Code.

Reading the Code wording carefully, it is clear that Section 1004.2.2.1 of the 2002 NYS Code is not an “allowance” but rather a requirement: “In occupancies other than Groups H-1, H-2 and H-3, the common path of egress travel shall not exceed 75 feet.” Thus, the section does not “allow a 75 foot common path of travel before access to two exits is required,” as you state, but rather requires that such common paths of travel “not exceed 75 feet.” The Code requirement for a limit on common paths of travel in no way permits you to disregard equally valid requirements in the Code requiring that two exits be placed a minimum distance apart.

Under your reasoning, it is not even clear why two exits would be needed, since that requirement is in the same Code section as the requirement that the two exits be “placed a distance apart…” Since you’ve discarded the latter rule, why not the former as well? And while we’re discussing exit requirements, why not also discard the requirements for minimum exit width. For example, in a space with 100 occupants, each requiring 0.15 inch of exit width or 15 inches total, why not do away with the two-exit requirement since a single 36-inch door seems to satisfy this provision?

The point is that all of these separate requirements must be met: the common path of travel cannot exceed 75 feet and there must be two exits and the two exits must be separated by a Code-specified minimum distance and the total exit width must also comply with the Code. Satisfying one of these requirements is not sufficient. All must be satisfied.

According to your logic, there would be no need for a second remote exit in Room 157 E. Sibley Hall — this was one of the spaces subject to a lawsuit brought by (and lost by) Cornell — since the common path of travel from the most remote corner of that room to a point outside with two separate egress paths is no greater than 75 feet. Are you willing to re-argue that case as well?

Please reconsider your judgment. The safety of Milstein/Sibley/Rand occupants is at stake. Are you really suggesting that satisfying the requirements for common path of travel allows you to violate Section 1004.2.2.1 of the 2002 NYS Code (equivalent to Section 1015.2.1 of the 2009 IBC)?

And for the architects involved in this decision: note that you cannot rely upon the opinion of the City of Ithaca Code officials to defend yourself in the event of any litigation. You, and not the Code officials, are charged and licensed by the State of New York to protect the health and safety of building occupants. Please don’t wait for a disaster to occur: act now. The architects working for OMA should be particularly sensitive to the real risk of fire in buildings that they design or renovate.

2. On a separate but related note, how do you compute a limit of 349 occupants for two exits? Why isn’t the limit equal to 500 (assembly occupancy with “standing space”). The crit space would certainly be large enough to accommodate that occupant load — that is, if it had two remote exits, which it doesn’t.

3. And why aren’t three exits required given the size and occupancy of this space? [see Update #5 below]

Jonathan

———————

[Update #3: March 8, 2012] Here is what I received 3/8/12 from the City of Ithaca Building Department in response to my last detailed email: “I respectfully disagree with your code interpretation. Take care, Mike.” Here is what I emailed back (also copied to Dean Kleinman at Cornell and a host of others, who have, thus far, remained silent):

Mike,

Here are the facts — not “interpretations.” I’m referencing the 2009 IBC, but the same language and intent appear in the NY State Codes.

1. IBC Section 1014.3 requires that any common path of egress travel not exceed 75 feet, with “common path of travel” defined as that portion of exit access which the occupants are required to traverse before two separate and distinct paths of egress travel to two exits are available.

2. IBC Section 1015.1 requires that two exits be provided for spaces with more than 49 (or 50 in the older versions of the Code) occupants — or three exits for spaces with more than 500 occupants. The determination of number of occupants is not discretionary, but is governed by the floor area of the space and its occupancy classification, per IBC Table 1004.1.1. For example, the crit space in Milstein Hall must be designed for more than 500 occupants since it can be occupied, and is intended to be occupied, as “assembly standing space” with 5 square feet per occupant, and it has a floor area greater than 501 x 5 = 2505 square feet.

3. IBC Section 1015.2.1 requires that where two exits are required, they be placed at a distance apart equal to not less than 1/3 the length of the maximum overall diagonal dimension of the area served.

That’s all. There is nothing in the Code that says you can ignore any of these requirements for any reason relevant to this discussion. This is not my “interpretation.” These are facts taken directly from the Code. Do you “respectfully disagree” with any of these facts?

In contrast, you have not referenced a single sentence in the Code that indicates, hints, or suggests in any way that the “remoteness” requirement of IBC Section 1015.2.1 can be ignored. Unless you can point to some language in the Code that supports your position (and you can’t, because there is no such language in the Code), these spaces in Milstein and Sibley Hall are being occupied illegally, presenting a danger to the faculty, students, and staff who use them.

Your prior suggestion that the common path of travel requirement of IBC Section 1014.3 allows spaces to be configured in violation of the “remoteness” requirement of IBC Section 1015.2.1 is not supported by any Code language and is contradicted by very specific Code language. To invent something out of thin air that contradicts specific Code language is not an “interpretation.” Rather, it is a flagrant abuse of authority. I again ask that you reconsider, and at least obtain a “second opinion” from New York State or ICC Code experts before closing the book on this issue.

Jonathan

[Update #4: March 11, 2012] I’ve already shown that the argument about the Milstein crit space advanced by the City of Ithaca Building Department — that meeting the common path of travel limit of 75 feet exempts one from any requirement that the two exits be remote from each other — has no basis in the Code and, in fact, is dangerous and incorrect.

I wish to note, however, that even that incorrect logic cannot be sustained in this particular case: the Milstein Hall crit space, especially with its permanent partitions, does not even come close to meeting the common path of travel limit of 75 feet.

So the space is actually doubly dangerous, being noncompliant under both of these Code sections.

[Update #5: April 19, 2012] I finally figured out why Ithaca Deputy Building Commissioner Mike Niechwiadowicz insists that the crit space under the Milstein Hall dome be limited to 349 occupants, even though the standard limit for two exits is 500 occupants. The 2002 NYS Building Code, while based on the International Building Code, has a special NYS-only provision requiring a third exit in Assembly occupancies with 350 or more occupants. None of this matters, however: there are not two remote exits in the space, so the point is moot. And even if there were two remote exits, the space is still noncompliant since — based on its occupancy and floor area — three exits are required. The Code does not permit a room to have insufficient exits merely because some sign is posted limiting occupancy to an unrealistically low number. This strategy may well be employed in existing buildings that need to comply with modern building codes, but it is not permitted for new construction.

Milstein’s studio floor

The seventh in my ongoing series of Milstein Hall construction videos is now online:

The index for all my Milstein Hall contruction videos is here.

Milstein Hall, at Cornell University, was designed by Rem Koolhaas and OMA.

update on egress and mezzanine in Milstein Hall

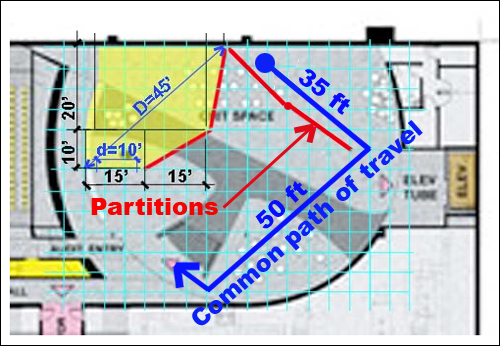

Two issues have emerged with the construction of partitions in the crit space of Milstein Hall (Rem Koolhaas, OMA architects), under the concrete dome.

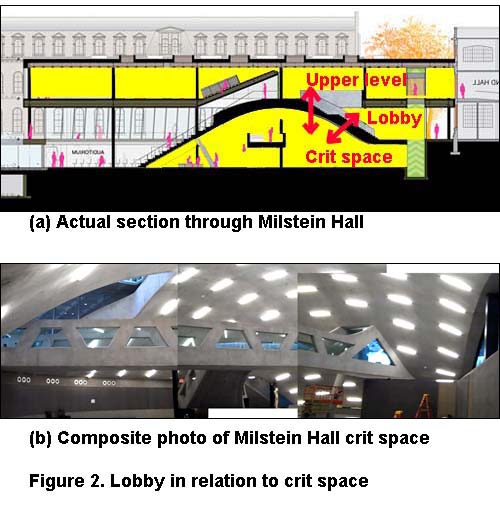

1. In a prior post, I mentioned that the interconnected spaces in Milstein Hall should probably not be permitted under the 2002 Building Code of NYS, since such an open geometry containing an unenclosed egress stair is legal only if no more than two stories are connected. Only if the “first-floor” lobby level is called a mezzanine — so that it becomes part of the lower-level space, reducing the number of stories from three (basement, first, and second) to two (first and second only) — do these interconnected spaces appear to comply with the Code.

However, the definition of a mezzanine has two requirements: it must have no more than one third the area of the room or space it is in; and it must be actually “in” the room or space it is in (the lower level crit space under the dome). I discussed the ambiguity of the requirement for the mezzanine to be “in” the crit space, but also warned that the whole pretense would fall apart if the crit space was subdivided in the future, since in that case, the lobby might no longer qualify as a mezzanine and the openings connecting three stories would clearly not be legal.

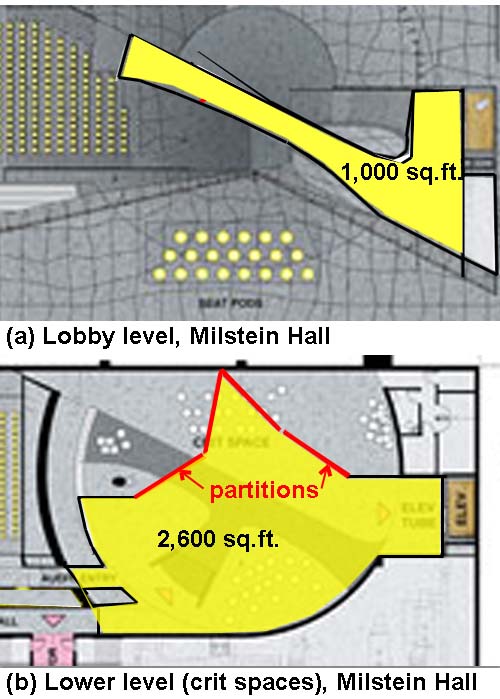

Well, the future is now. Partitions are being finished within the lower-level crit space (see Figure 1) that subdivide the larger space into smaller rooms or spaces. As can be seen in Figure 2, the largest of these newly-subdivided spaces is approximately 2,600 square feet, while the lobby is approximately 1,000 square feet. Since the lobby has an area that is more than one third that of the space below, it no longer qualifies as a mezzanine.

In other words, the lobby must be considered as a separate story, and the openings in what are now three interconnected stories become noncompliant, if they weren’t already.

2. The second issue has to do with required egress from spaces with more than 50 occupants. In a prior post I described the unacceptable location of exits in the crit space, since they are too close to each other to qualify as separate exits under the Code. Now that partitions are being constructed to subdivide the crit space, the same problem occurs in the smaller rooms being created.

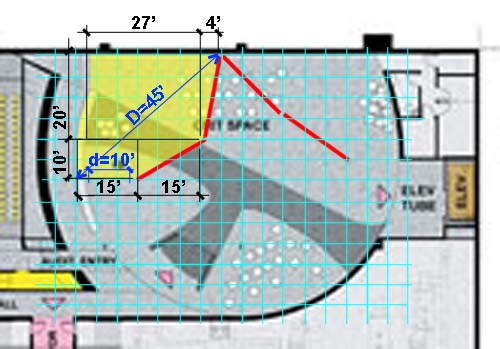

The Code requires that any room with more than 50 occupants have two separate exits, and that these exits be a distance apart no smaller than one third the diagonal length of the room. To determine the number of occupants, one identifies the type of use, in this case an “assembly” occupancy with chairs that are not fixed. For such a use, the Code assigns 7 square feet per occupant. The area of the subdivided room in question, shown with a yellow tone in Figure 3, can be calculated as follows:

27 x 20 = 540 square feet

0.5 x 20 x 4 = 40 square feet

10 x 15 = 150 square feet

0.5 x 10 x 15 = 75 square feet

The total room area = 540 + 40 + 150 + 75 = 805 square feet.

Assuming 7 sq.ft. per occupant, the room must be designed for 805 / 7 = 115 occupants.

Even if the room had tables and chairs, like a classroom with 15 sq.ft. per occupant, it would still need to be be designed for 805 / 15 = 54 occupants.

Using either of these assumptions, two exits are required. The partitions only provide one exit. And this single exit is not wide enough to qualify as two exits based on its length compared to the diagonal length of the room.

The fact that these permanent partitions are movable shouldn’t change any of the conclusions drawn here. They are able to be configured in ways that are sometimes compliant and sometimes noncompliant, but they must be judged based on all possible geometries, especially those that put people and property in danger.

implausible egress interpretation

[Updated below] Aside from limiting the fuel within a given fire area through various compartmentation strategies, a fundamental component of all fire safety requirements is to provide protected paths of escape (egress) for building occupants in the event of a fire incident. The number and characteristics of these so-called means of egress depends on several variables, including the type of occupancy and the number of occupants. The large critique (crit) space under the dome of Milstein Hall (Rem Koolhaas, OMA architects) does not seem to meet these egress requirements.

The number of occupants in the crit space should be taken as the larger of (a) the actual number of anticipated occupants or (b) a number found by dividing the floor area of the space by the tabular floor area per occupant found in Table 1003.2.2.2 of the 2002 Building Code of NYS (Maximum floor area allowances per occupant). Following are the tabular values for assembly spaces — and the crit space certainly seems to count as an A-3 assembly space:

• Chairs only, but not fixed = 7 square feet per occupant

• Standing space = 5 square feet per occupant

• Unconcentrated, i.e., tables and chairs = 15 square feet per occupant

The most generous interpretation for the occupant use of this space would be “chairs, not fixed” with an allowance per occupant of 7 square feet. This corresponds to the reality of such critique assembly spaces, which can be crowded with students and faculty reviewers. Assuming an approximate floor area of 3,600 sq. ft. (the actual area may well be closer to 4,000 sq.ft.), the number of occupants in this space is 3600 / 7 = 514.

For any Group A or B space with 51 or more occupants, at least 2 exits from the space are required. Per Table 1005.2.1, three exits are required for 501-1000 occupants. Therefore, at least two, and possibly three, exits are needed from the crit space. It’s hard to imagine having more than 500 occupants in that space, as there are not that many architecture students in the entire program, but even with less than 500 occupants the requirement for two exits appears, at first glance, not to be met.

According to Section 1004.2.2.1 of the Code, and assuming that only two exits are needed, these two exits must be “placed a distance apart equal to not less than one half [or one third for this sprinklered space, per exception] of the length of the maximum overall diagonal dimension of the building or area to be served.”

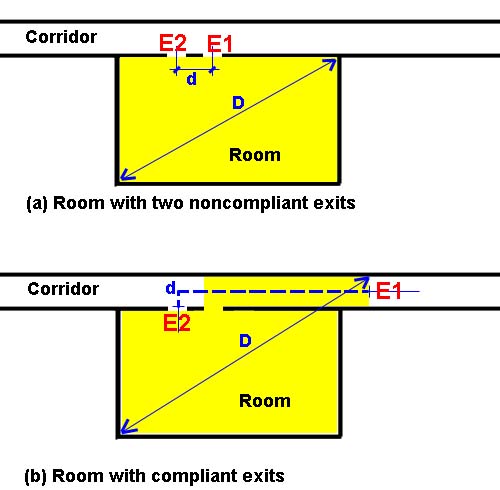

As can be seen in Figure 1a, two exits from a room with more than 50 occupants cannot be placed next to each other, since the distance, d, must be at least one third the length of the diagonal distance, D. But what if we pretend that the room actually extends into the corridor, as shown by the shaded yellow area in Figure 1b? In that case, the two exits are now still not compliant, since even though one of them, E1, has been “moved” far enough away such that the distance, d, is now greater than one third of the distance, D. Nothing has changed to make the room safer, but and the exits are now still not compliant.

Of course, one needs One would need to stretch beyond plausibility the definition of a corridor to make this work. A corridor is a type of exit access, which the Code defines as follows: “That portion of a means of egress system that leads from any occupied point in a building or structure to an exit.” It seems clear that the corridor shown in Figure 1 really is acting as a corridor, and not as a part of the room. But the main point is this: even if the corridor is envisioned as “part” of the room, the egress situation remains noncompliant, because the occupants of the space still need to pass through what amounts to a single exit, rather than having two exits available. [see update 3 below] But how does this apply to the crit space in Milstein Hall?

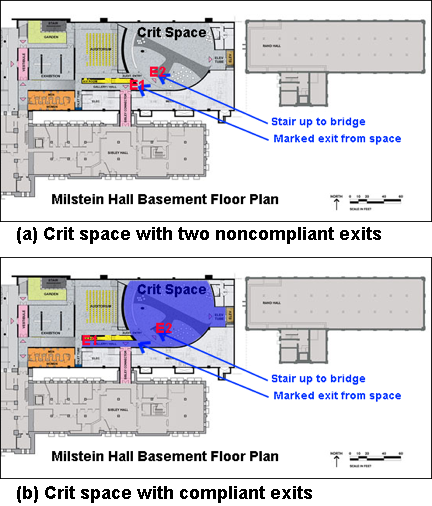

If the second exit from the crit space is assumed to consist of the unenclosed stair leading to the bridge above the crit room space, this second exit (marked E2 in Figure 2) does not appear to conform to the requirement that it be a minimum distance from the first exit (marked E1) — this distance determined by dividing the maximum diagonal length of the room by three.

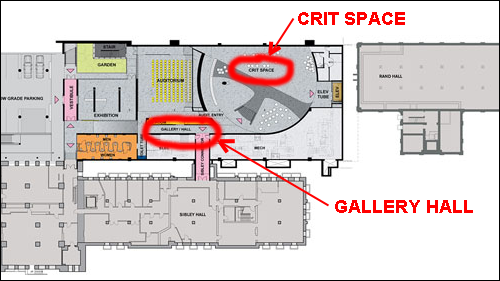

To solve this problem, the architects for Milstein Hall have attempted to use used the trick outlined above: as explained to me by Cornell’s Project Director for Milstein Hall, the crit space actually extends into what appears to be the corridor leading to the exit (see Figure 2b with the extent of the crit space shown in blue). In fact, there are even felt pin-up walls in this “corridor” to lend credence to this interpretation. Even so, the safety of the crit space appears to have been compromised by this imaginative Code interpretation.

[Update: Oct. 13, 2011] As I describe in a later post, the smaller crit spaces formed by new partitions also have egress problems.

[Update 2: Oct. 13, 2011] One might have more sympathy for the architects’ contention that the crit space actually extends into the corridor if they had indicated this intention on their plans. In fact, they label the corridor separately from the crit space (calling it a “gallery/ hall”) as can be seen in this annotated screen shot taken from Cornell’s Milstein Hall website:

[Update 3: March 1, 2012] The deleted text and bold-face additions above are intended to clarify the point that I was trying to make: that the crit space under the dome in Milstein Hall (or any similarly configured space with more than 49 occupants) is noncompliant with egress regulations in building codes. This judgment was recently supported by a Code expert from the International Code Commission (which publishes the International Building Code upon which the New York State Building Code is based); I will publish his written opinion as soon as I receive it [the Code opinion can be found here].

milstein hall and its interconnected spaces

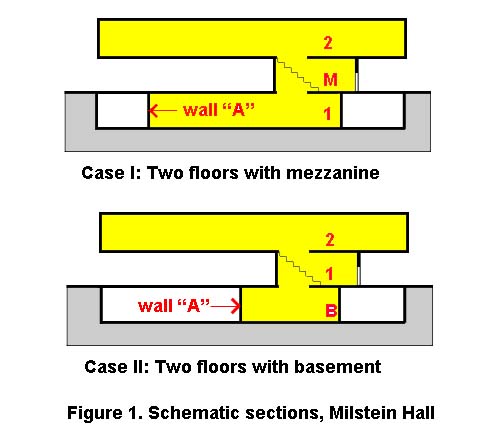

Milstein Hall at Cornell (Rem Koolhaas, OMA architects) contains what appears to be three floors, all interconnected with an opening through which passes an unenclosed egress stair. Such a condition, unless it is designed as an atrium with special smoke control measures, would not be permitted under the New York State Building Code — see my discussion of holes in floors.

Milstein Hall's interconnected spaces -- crit space below, lobby/bridge in the middle, and studios above -- can be seen in this image

I asked the Project Director for Milstein Hall how such an interconnected opening was possible, since the interconnected spaces were clearly not designed as an atrium. He explained that, contrary to appearances, the building only has two stories with no basement: what appears as the basement is actually the first floor; what appears as the first floor is actually a mezzanine; and only the second floor is really what it appears to be — the second floor. Mezzanines need to be no more than one-third the floor area of the room or space they are in, and the first-floor lobby of Milstein did appear to be no bigger than one-third the floor area of the crit space under the dome to which it is connected.

However, while the interconnected openings in Milstein Hall appear at first glance to meet the “letter” of the Building Code, they may well be noncompliant.

Comparing Case I and Case II in Figure 1, one can see that the entire rationale for allowing an unenclosed egress stair from the second floor to the mezzanine lobby depends on the relative area of the space defined by what I have schematically called wall “A.” If wall “A” is placed in such a way that the area of the space it forms is at least 3 times bigger than that of the lobby (Case I), then the lobby can be counted as a mezzanine, and the egress stair is then technically within an unenclosed opening connecting only two stories, thereby conforming with exception 8 or exception 9 in Section 1005.3.2 of the 2002 New York State Building Code.

However, if wall “A” is moved so that the area of the space it forms is less than 3 times the size of the lobby (case II), then the lobby cannot be called a mezzanine. It now becomes the first floor, and the same openings and egress stair become noncompliant.

This seems entirely irrational, since Case II, with less floor area to house combustible products and a smaller number of occupants than Case I, is nevertheless noncompliant, whereas Case I, with a larger area and therefore more occupants and potentially combustible products, would be deemed compliant.

It seems probable either that the writers of the Code never anticipated that their definition of mezzanine would be exploited in this way, or that other aspects of the mezzanine definition make this geometry noncompliant.

The definition of mezzanine, found in Section 502 of the 2002 Code, states that it must have “a floor area of not more than one-third of the area of the room or space in which the level or levels are located.” The key word here is “in.” The mezzanine must be “in” the room or space, not outside the room or space with an opening that connects them. Now, one might debate what exactly the meaning of the word “in” is (by analogy to Bill Clinton insisting that a proper interpretation of his prior testimony “depends on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is”). As can be seen in Figure 2, common sense would suggest that the lobby is not “in” the dome. Both the section (Figure 2a) and the composite photo (Figure 2b) show clearly that the concrete structure of the dome creates a distinct “room” or “space” and that the lobby (pictured through the hole in the dome visible at the left of Figure 2b) is completely outside that space.

It is possible (along the lines advocated by Clinton) to define “in” topologically rather than by recourse to “common sense”; in that case the lobby can indeed be tested as a mezzanine “within” the dome “crit space.” In other words, we could draw a continuous contour line through the opening connecting the two spaces and call the resultant figure a single space. But the Code is fairly careful about the prepositions it deploys. If the intent were to allow a mezzanine to have any interconnected relationship to a room or space, other words or phrases could have been chosen instead of “in” or “within.” The Code does not describe a mezzanine as being “next to” or “adjacent to” or “connected to” some other room or space: it specifically says that a mezzanine must be “within” a room.

Still, this is admittedly ambiguous. The commentary to the 2009 IBC doesn’t really help: “So as not to contribute significantly to a building’s inherent fire hazard, a mezzanine is restricted to a maximum of one-third of the area of the room with which it shares a common atmosphere.” Here, the phrase “common atmosphere” has two purposes: first, it signals that the mezzanine must be somehow contiguous with the space it is in; second, it excludes any “enclosed portion of a room” in computing “the floor area of the room in which the mezzanine is located.” Having a “common atmosphere” appears therefore to be a necessary, but not sufficient condition. The mezzanine must also be “in” the room or space, which again brings us back to the question of what “in” is.

But this much is true: if the lobby space cannot be called a mezzanine, then it counts as a story. In that case, the interconnected openings are noncompliant, as they meet none of the exceptions for shaft enclosures outlined in Section 707.2 of the 2002 Code. And even if the lobby is now granted the status of mezzanine, the crit space under the dome becomes locked into its current geometry forever: it can never be reconfigured, for example, into a series of smaller rooms, since the lobby would then exceed its maximum floor area qua mezzanine and would revert back to being a separate story. The opening connecting what would now be three interconnected stories would be noncompliant.

[Update: Oct. 13, 2011] As I describe in a later post, the crit space has now been subdivided into a series of smaller rooms, appearing to make both the lobby noncompliant as a mezzanine, and the interconnected stories with an unenclosed egress stair noncompliant according to the various allowable exceptions for shaft enclosures.